Statement on Proposals to Restrict Shareholder Voting

Thank you, Mr. Chairman, and thanks to Commissioner Roisman, Division Director Bill Hinman, and especially the tremendous Staff in the Division of Corporation Finance for their hard work in advance of today’s meeting. And congratulations to all of my colleagues who watched the Washington Nationals earn their first World Series title last week.[1]

Today the Commission proposes rule changes that would limit public-company investors’ ability to hold corporate insiders accountable. We haven’t examined our rules in this area for years, so updating them makes sense—and these issues have been thoughtfully debated for decades.[2] But rather than engage carefully with the evidence produced by those debates, today’s proposal simply shields CEOs from accountability to investors. Whatever problems plague corporate America today, too much accountability is not one of them, so I respectfully dissent.

I. Tilting Corporate Elections Toward Management

Holding executives accountable for the way they run America’s corporations is difficult and expensive, and investors lack the time and money to do it. That’s why investors use proxy advisors, who make recommendations about how shareholders should vote. Today’s proposal imposes a tax on firms who recommend that shareholders vote in a way that executives don’t like.

To see why, consider a proxy advisor deciding how to advise shareholders in a proxy fight driven by poor performance. Recommending that investors support management comes with few additional costs under today’s proposal.[3] But firms recommending a vote against executives must now give their analysis to management, include executives’ objections in their final report, and risk federal securities litigation over their methodology. Taxing anti-management advice in this way makes it easier for insiders to run public companies in a way that favors their own private interests over those of ordinary investors.

Proxy advisors play an important role in striking the right balance in allocating power between corporate executives and investors. And it is, indeed, a balance, which is why I’ve supported common-sense ideas like rules ensuring that proxy advice is based on accurate facts.[4] But under today’s proposal, the SEC is interfering in decades-long relationships between investors and their advisors in a way that will significantly skew voting recommendations toward executives. That will be especially true in cases, such as investor proposals to strengthen the link between CEO pay and performance, where proxy advisors have historically engaged in the careful, firm-specific analysis that such proposals require.[5]

Tilting corporate voting toward incumbent management in this way will have consequences—including reducing the already-scant competition among proxy advisors—that we could and should have studied extensively before making any other changes in the balance of power between CEOs and shareholders.[6] But instead my colleagues are also proposing changes to the shareholder proposal process that will further insulate corporate managers from accountability.

II. Taking CEO Accountability off the Corporate Ballot

Today’s release also significantly raises the vote required for resubmission of a shareholder resolution. To understand the effects of that rule on the balance of power between insiders and investors, we should examine the kinds of proposals that will be taken off the ballot—and their effect on firm value. Today’s release does not even attempt to do that. Instead, the proposal simply assumes that high levels of support indicate a good proposal—and that lower levels of support suggest that a proposal is bad.

That has not been the SEC’s historical approach to shareholder proposals—and for good reason. Because investor interest in a subject takes time to coalesce, the Commission has long recognized that short-run voting results are not the only factor in determining a proposal’s merits.[7] For example, when we first developed rules requiring disclosure of executive pay, the Commission’s release used results from shareholder proposal votes at nine public companies as a basis for our new rule. All but one of those executive pay proposals fell short of the third resubmission threshold my colleagues propose today.[8] The assumption that vote totals reflect the merits of proposals risks depriving investors and the Commission of information that has long produced crucial transparency on corporate governance matters.

A better approach is to examine how these new rules would affect shareholder proposals that enhance value by making management more accountable to investors. So that’s what my Office did. We dug into the data to see what kinds of investor initiatives would be excluded by today’s rule. And the evidence shows that the proposed changes remove key CEO accountability measures from the ballot.

Take, for example, proxy-access proposals—initiatives to allow significant shareholders to put their own candidates up for election to the board. These are popular proposals: they hold underperforming executives’ feet to the fire with a more realistic threat of a contested election. The evidence shows that these proposals often add value for shareholders over the long run.[9] But today’s rule would remove 40% of these proposals from the ballot after three tries—and keep them off for three years.[10]

Or consider shareholder proposals to limit CEOs from selling stock they receive as compensation. Between 2004 and 2018, more than 100 U.S. companies received these proposals. Executives at these companies cashed out a total of $7 billion in stock in the year when investors raised these proposals.[11] Here, too, research suggests that these proposals probably enhance firm value over the long run.[12] But under today’s rule, more than half of these proposals would be removed from the ballot after three votes. Whatever one’s personal view of the merits of these particular investor initiatives, all should agree that we should have considered the costs and benefits of removing them from the ballot before proceeding. Yet the release offers no analysis of that question at all.

There are other wide-ranging consequences that the release does not carefully consider. Raising our resubmission thresholds would shift the landscape of negotiations between investors and management that often lead to voluntary resolutions that satisfy both sides.[13] Raising the thresholds at the same time we are imposing a tax on anti-management advice gives us no opportunity to observe the effects of that tax on the levels of support proposals should be expected to receive. And raising the thresholds at firms with dual-class structures would make it easier for executives at those companies to use their outsized voting power to keep shareholder proposals off their ballot.[14]

III. The Path Ahead

Today’s proposal is especially regrettable because, to the degree we have identified a problem worth solving, there’s a straightforward alternative supported by a close review of the evidence. If we’re worried about the classic problem that arises when one person is empowered to spend someone else’s money, we should ask whether our shareholder-proposal rules allow a few investors to impose excessive costs on ordinary investors. And we should study and propose a rule designed to solve that problem.[15]

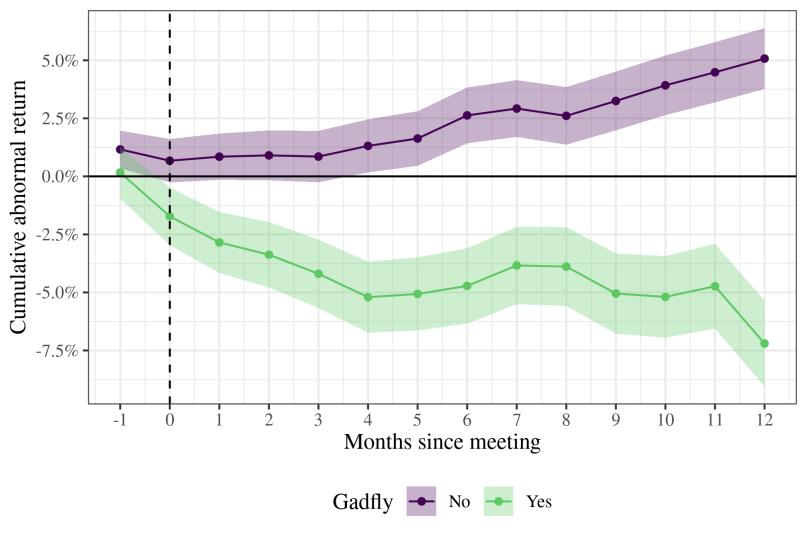

Important work has shown that many investor initiatives are advanced by a small group of individuals sometimes derisively called “gadflies.”[16] And recent research suggests that the long-run value implications of those proposals may be meaningfully different from the effects of other kinds of proposals.[17] As I’ve said, there is simply no analysis of the long-run implications of including proposals on the corporate ballot in today’s release. So my Staff and I examined the evidence to see what we could learn about the link between the shareholder proposal process and the actual interests of ordinary buy-and-hold investors.

The results are striking. On average, we show, inclusion of shareholder proposals from individual investors by an American public company tends to be associated with long-term value increases. But so-called gadfly proposals—those brought by the ten most frequent individual submitters each year—appear to have the opposite effect, leading to long-run value decreases for ordinary investors:[18]

Figure 1. Link Between Proposal Inclusion and Long-Run Value, by Proponent Type[19]

Exactly how to address this evidence is a hard question deserving close study.[20] We could, for example, pursue rules that encourage individual shareholders to focus their limited resources on a smaller number of companies or issues.[21] Any such rules would, of course, have to balance those considerations with the increasingly limited supply[22] of investors willing to spend time and money holding CEOs to account.[23] Unfortunately, today’s release doesn’t engage with those questions—instead adopting pro-management changes that swat a gadfly with a sledgehammer.

* * * *

Today’s proposal ignores decades of debate about the role of the Commission in striking the right balance between corporate executives and the investors they serve. That debate, and the evidence it has produced, has a great deal to teach us about how to make sure shareholder democracy creates long-run value for ordinary American investors.[24]

Fortunately, however, today’s proposal is just that: a proposal. I look forward to working with my colleagues on the Commission, the Staff, and in the Division of Economic and Risk Analysis over the coming months to further engage with my Office’s analysis. I am grateful to the Staff for their work on today’s proposal. And I hope shareholders of all kinds will come forward to engage with the Commission on how to best help American investors hold corporate executives accountable.

[1] Until last month, the last time a World Series game was hosted in Washington was in 1933—an important year for federal securities law. Securities Act of 1933, 15 U.S.C. §§ 77a et seq. In light of my Bronx heritage, my Washington friends have asked about my reaction to their new title. I’d merely note that, to catch my Yankees, the Nationals have only twenty-six more titles left to go. See Doris Kearns Goodwin, Wait Till Next Year (1997).

[2] The generation-long debate on the appropriate balance between insider and investor power has produced some of the most seminal articles in corporate law. Martin Lipton, Takeover Bids in the Target’s Boardroom, 35 Bus. Law. 101 (1979); Lucian Bebchuk & Marcel Kahan, A Framework for Analyzing Legal Policy Towards Proxy Contests, 78 Cal. L. Rev. 1071 (1990); John C. Coffee, Jr., Liquidity Versus Control: The Institutional Investor as Corporate Monitor, 91 Colum. L. Rev. 1277 (1991); Bernard Black, The Promise of Institutional Investor Voice, 39 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 811 (1992); Roberta Romano, Making Institutional Investor Activism a Valuable Mechanism of Corporate Governance, 18 Yale J. Reg. 175 (2001); Henry Hansmann & Reinier Kraakman, The End of History for Corporate Law, 89 Geo. L.J. 439 (2001); Stephen M. Bainbridge, Director Primacy: The Means and Ends of Corporate Governance, 97 N.W. U. L. Rev. 547 (2003); Marcel Kahan & Edward B. Rock, The Hanging Chads of Corporate Voting, 96 Geo. L.J. 1227 (2008); Ronald J. Gilson & Jeffrey N. Gordon, Activist Investors and the Revaluation of Governance Rights, 113 Colum. L. Rev. 863 (2013); Zohar Goshen & Richard Squire, Principal Costs: A New Theory for Corporate Law and Governance, 117 Colum. L. Rev. 44 (2017). For perspective on how rushed and incomplete the analysis underlying today’s actions is, note that among all of these authors—all leading thinkers in the bar and academy on the subject—just one is even cited in today’s release.

[3] To be sure, the proposal technically imposes the same requirements regardless of the content of the advice. Securities and Exchange Commission, Proposed Rule: Amendments to Exemptions from the Proxy Rules for Proxy Voting Advice (Nov. 5, 2019), at 46-47 (“The proposed amendments to Rule 14a-2(b) [apply] regardless of whether the advice on the matter is adverse to the registrant’s own recommendation.”). But the real costs of today’s new regime lie in considering the issuer’s feedback, including the issuer’s response in the proxy advisor’s report, and facing litigation from an issuer angry about the methodology used to provide anti-management advice, see id. at 71-72, and for present purposes I make the unremarkable assumption that corporate managers reviewing a friendly proxy-advisor recommendation will not impose these costs on the advisor issuing that opinion.

[4] Gillian Tett, Billy Nauman & Patrick Temple-West, Mining for Good; Tax Avoidance; Proxy Advisers on Notice, Fin. Times (July 24, 2019).

[5] Between 2004 and 2018, investors filed 191 proposals at public companies on the link between CEO pay and performance. Management recommended that shareholders vote “no” on 100% of those proposals; Institutional Shareholder Services recommended investors vote “no” on 40% and “yes” on 60%. Under today’s proposed rule, recommending that investors vote for proposals like these will be exceedingly costly. For starters, the firm will need to prepare a draft report for distribution to management, and in light of executives’ universal opposition to these proposals can and should expect pointed and lengthy feedback. The proxy advisor must then consider this feedback and decide whether and how to incorporate it into a report for investors. Then, the advisor will be required to send the final report to issuers and, if there is still disagreement, include management’s view in that report. And all of this will occur in the shadow of the threat of the issuer bringing federal securities litigation over disagreements with the advisor’s data or methodology. The result, of course, will be fewer recommendations against management’s view.

[6] Those concerned about the influence of the two principal proxy-advisory firms should consider that today’s actions may lead to further consolidation in the industry—handing even more power to the largest player. See Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Statement on Proxy-Advisor Guidance (Aug. 21, 2019). Unfortunately, the economic analysis in today’s release fails to address this concern—or even cite an important recent paper showing the benefits of competition in this area for investors and issuers alike. See Tao Li, Outsourcing Corporate Governance: Conflicts of Interest Within the Proxy Advisory Industry, 64 Mgmt. Sci. 2951 (2018).

[7] There are many reasons for this well-known fact, including the collective-action problems shareholders face—and the voting tendencies of large institutional investors. Ryan Bubb & Emiliano Catan, The Party Structure of Mutual Funds (working paper 2018) (noting that traditional funds “support management at much greater rates” than other institutions); Alon Brav, Wei Jiang & Tao Li, Picking Friends Before Picking (Proxy) Fights: How Mutual Fund Voting Shapes Proxy Contests (working paper 2018).

[8] Executive Compensation Disclosure, Exch. Act. Rel. No. 33-6940, 57 Fed. Reg. 29,582 tbl. 1 (1992) (reporting the results of executive-pay disclosure proposals with support as low as 5.6%).

[9] Compare Jonathan B. Cohn Stuart L. Gillan & Jay C. Hartzell, A (Dodd)-Frank Assessment of Proxy Access, 71 J. Fin. 1623 (2016) and Bo Becker, Daniel Bergstresser & Guhan Subramanian, Does Shareholder Proxy Access Improve Firm Value? Evidence from the Business Roundtable Challenge, 56 J. L. & Econ. 127 (2013), with Thomas Stratmann & J.W. Verret, Does Shareholder Proxy Access Damage Share Value in Small Publicly Traded Companies?, 64 Stan. L. Rev. 1431 (2012). These studies, of course, focus on the costs and benefits of a mandatory proxy-access rule, rather than the company-by-company regime undermined by today’s release.

[10] To calculate this figure, we extract data on shareholder proposals from the ISS Analytics database for each year from 2004 to 2018—a total sample of 8,319 proposals. Then, we manually clean and normalize proponent names, following Nickolay Gantchev & Mariassunta Giannetti, The Costs and Benefits of Shareholder Democracy (working paper 2019), to identify frequent submitters. Finally, we compute support for each category of proposal, conditional on the number of times each proposal has been submitted, to evaluate the impact that today’s proposed resubmission thresholds would have had on ballot exclusion had those thresholds been applied in previous years.

[11] We calculate this figure by extracting data from the Thomson Form 4 database and computing net selling as the dollar amount of shares sold during the calendar year in which a company faced a proposal of this kind.

[12] Jun-Koo Kang & Limin Xu, Executive Stock Ownership Guidelines and Debtholder Wealth (forthcoming 94 The Accounting Review ____ (2019)).

[13] Eugene F. Soltes, Suraj Srinivasan & Rajesh Vijayaraghavan, What Else Do Shareholders Want? Shareholder Proposals Contested by Firm Management (Harv. Bus. Sch. Working Paper, 2017) (finding, in a recent dataset, that some 16% of contested proposals are either withdrawn by the submitting shareholder or implemented by the firm following discussions on both sides).

[14] For example, just last year Facebook’s outside investors overwhelmingly voted to change its dual-class structure. Facebook, Inc. Form 8-K (May 30, 2019) (reporting that, at the company’s last annual meeting, some 82% of votes not controlled by Facebook’s founder voted in favor of such a change). That proposal has previously been brought several times. Because of Facebook’s dual-class structure, support from more than 80% of outside investors amounted to just 24.5% of the overall vote—meaning that, under the rules in today’s release, this proposal will soon be removed from Facebook’s ballot for three years.

[15] I agree with those of my predecessors who have emphasized that careful, data-driven analysis of these questions, rather than resort to ideological intuition, is especially important in the hotly contested area of balancing the power of corporate insiders and investors. See, e.g., Commissioner Paul S. Atkins, Shareholder Rights, the 2008 Proxy Season, and the Impact of Shareholder Activism (remarks at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, July 2008) (correctly noting that “[c]ritical thinking about costs and benefits ought to be at the center of the Commission’s regulatory philosophy” in the context of proposed reforms to the rules addressed in today’s release).

[16] James R. Copland, Manhattan Institute, Frequent Fliers: Shareholder Activism by Corporate Gadflies (2014) (providing evidence regarding individual investor proposal activity); see also Steven Davidoff Solomon, Grappling with the Cost of Corporate Gadflies, N.Y. Times DealBook: The Deal Professor (Aug. 19, 2014) (noting that public companies spend substantial sums of investor funds grappling with these proposals).

[17] See Gantchev & Giannetti, supra note 10 (“[M]any proposals are submitted by the same few ‘corporate gadflies,’ individuals without organizational capabilities to analyze a large number of firms. These proposals, if supported by a majority of the votes cast and subsequently implemented, appear to destroy shareholder value.”).

[18] Using the data described supra note 10, and the method in Gantchev & Giannetti, supra note 10, we focus only on close or contested votes. Like Gantchev & Giannetti, we define “close” votes as those that fall within twenty percentage points of attracting majority support, and contested votes as those where management’s recommendation conflicts with that of one or both of the major proxy-advisory services.

[19] Notwithstanding the rigorous methodological choices in Gantchev & Giannetti, supra note 10, I need not and do not draw the causal inference that proposal inclusion causes the value effects depicted in Figure 1. The evidence may instead pick up a selection effect: that certain proponents are more likely to target poorly performing companies, for example, or that those companies have other corporate governance features linked to long-term value effects. For present purposes, I note only that inclusion of certain proposals can be clearly associated with long-run value implications that matter for investors. In my view, evidence of this kind is critical in making policy choices like those we are proposing today.

[20] Today’s release does appear to address this issue more squarely when limiting individual investors to a single proposal at each company each year, Securities and Exchange Commission, Proposed Rule: Procedural Requirements and Resubmission Thresholds under Exchange Act 14a-8, Release No. 43-____ (November 5, 2019), at 38-39 (“We propose . . . to apply the one-proposal rule to ‘each person’ rather than ‘each shareholder’ who submits a proposal.”), but it is hardly clear that this rule will in fact have the intended effect, see infra note 20.

[21] Most research considering the question has concluded that individual shareholders’ limited resources, when compared to those of larger institutional investors, make identifying and advancing value-enhancing proposals unusually challenging. Gantchev & Giannetti, supra note 10; see also David F. Larcker & Brian Tayan, Stanford Closer Look Series, Gadflies at the Gate: Why Do Individual Investors Sponsor Shareholder Resolutions? (Aug. 11, 2016) (analyzing this question on the basis of interviews of nine individual activists and noting that individual shareholders “lack the resources of institutional investors”). The one-proposal-per-company-per-person limit in today’s proposal, see supra note 19, may thus have the unintended (and potentially damaging) consequence of encouraging these individuals to spread their work across more companies—a possibility that today’s release does not even mention.

[22] Compare Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen & Scott Hirst, The Agency Problems of Institutional Investors, 31 J. Econ. Persp. 89 (2017) and Lucian A. Bebchuk & Scott Hirst, Index Funds and the Future of Corporate Governance, 119 Colum. L. Rev. ____ (2019) (arguing that index funds have suboptimal incentives to monitor governance), with Ian Appel, Todd A. Gormley & Donald B. Keim, Passive Investors, Not Passive Owners, 121 J. Fin. Econ. 111 (2016) (“‘We’re going to hold your stock when you hit your quarterly earnings target. And we’ll hold it when you don’t. We’re going to hold your stock if we like you. And if we don’t. We’re going to hold your stock when everyone else is piling in. And when everyone else is running for the exits. That is precisely why we care so much about good governance.” (quoting Vanguard’s F. William McNabb III, making the contrary case)).

[23] Raising our shareholder-proposal resubmission thresholds to the levels in today’s proposal would also further empower America’s largest institutional investors, whose support will be increasingly necessary even to keep a contested proposal on the ballot. At a minimum, our release should grapple carefully with that implication before proposing changes of this magnitude. See John C. Coates IV, The Future of Corporate Governance Part I: The Problem of Twelve (working paper 2018).

[24] Today’s proposal reflects another missed opportunity for the Commission to address the bipartisan and “broad agreement that the Byzantine system that makes it impossible to know whether investors’ votes are being counted must be fixed.” Robert J. Jackson, Jr., Statement on Shareholder Voting (Sept. 14, 2018); see also David A. Katz, Wachtell, Lipton Rosen & Katz, Proxy Plumbing Fixes are Desperately Needed (Aug. 31, 2010).

Last Reviewed or Updated: Nov. 7, 2019