FORM 18-K/A

For Foreign Governments and Political Subdivisions Thereof

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, D.C. 20549

AMENDMENT NO. 7

to

ANNUAL REPORT

of

PROVINCE OF ONTARIO

(Canada)

(Name of Registrant)

Date of end of last fiscal year: March 31, 2012

SECURITIES REGISTERED*

(As of the close of the fiscal year)

|

Title of Issue

|

Amounts as to which

registration is effective

|

Names of exchanges

on which registered

|

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

Name and address of persons authorized to receive notices and

communications from the Securities and Exchange Commission:

Sean Sunderland

Counsellor (Intergovernmental Affairs)

and

Deputy Head of Section

Canadian Embassy

501 Pennsylvania Avenue N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20001

Copies to:

Jason R. Lehner

Shearman & Sterling LLP

Commerce Court West, 199 Bay Street

Suite 4405, P.O. Box 247

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5L IE8

* The Registrant is filing this annual report on a voluntary basis.

PROVINCE OF ONTARIO

The undersigned registrant hereby amends its Annual Report on Form 18-K for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2012 (the “Annual Report“) as follows:

The following additional exhibit is added to the Annual Report:

|

|

Exhibit (k)

|

Public Accounts of Ontario: 2012-2013 Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements

|

SIGNATURE

Pursuant to the requirements of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, the registrant has duly caused this amendment to the annual report to be signed on its behalf by the undersigned, thereunto duly authorized, at Toronto, Ontario.

PROVINCE OF ONTARIO

(Name of registrant)

|

September 16, 2013

|

By: /s/ Irene Stich

|

Name: Irene Stich

Title: Director, Capital Markets Operations

Capital Markets Division

Ontario Financing Authority

EXHIBIT INDEX

|

Exhibit (k):

|

Public Accounts of Ontario: 2012-2013 Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements.

|

EXHIBIT (k)

Public Accounts of Ontario 2012-2013

Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements

[The Ontario Coat of Arms]

Ministry of Finance

PUBLIC

ACCOUNTS

of

ONTARIO

2012–2013

Annual Report

and

Consolidated Financial

Statements

2012–2013 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS

To the Honourable

David C. Onley

Lieutenant Governor of Ontario

May It Please Your Honour:

The undersigned has the honour to present the Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2013, in accordance with the requirements of the Financial Administration Act.

Respectfully submitted,

/s/ Charles Sousa

The Honourable Charles Sousa

Minister of Finance

Toronto, September 2013

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword iii

Introduction 1

Guide to the Public Accounts 3

Annual Report 3

Supporting Volumes 4

Statement of Responsibility 5

FINANCIAL STATEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS

Overview 9

Analysis of 2012–13 results 11

Revenue 12

Investments in services, programs and infrastructure 14

Borrowing and financial position 18

Indicators of financial condition 19

Balancing the budget 21

Restraining growth in spending 21

Accountability and transparency in financial management and reporting 24

Delivering results 26

Better access to health care, better value for money 26

Keeping Ontario at the forefront of education and job creation 27

A cleaner, reliable electricity system 29

2012–13 Interim to Actual results 31

CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

Auditor’s Report 35

Consolidated Statement of Operations 37

Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 38

Consolidated Statement of Change in Net Debt 39

Consolidated Statement of Change in Accumulated Deficit 40

Consolidated Statement of Cash Flow 41

Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 42

Schedules to the Consolidated Financial Statements 67

Glossary 85

Sources of Additional Information 91

FOREWORD

I am pleased to present the Province of Ontario’s Public Accounts for the year 2012–13.

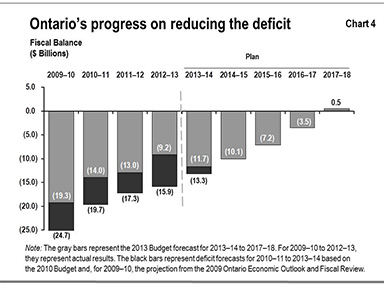

The new government is committed to creating jobs and building a strong and prosperous economy and to eliminating the deficit by 2017–18. This year the deficit is $9.2 billion, $5.6 billion lower than projected in the 2012 Budget, and a further reduction of $0.6 billion since the 2013 Budget.

This government has a plan for A Prosperous and Fair Ontario. It is focused on creating jobs and helping people with their everyday lives. Premier Kathleen Wynne and our government have a plan for jobs and growth that builds on strong economic fundamentals to enable Ontario’s economy to be more productive and more competitive.

The government’s plan includes a competitive tax system for business, making regulations smarter and less burdensome, and enhancing the stability and efficiency of capital markets. For example, by streamlining tax administration, Ontario businesses are saving more than $635 million per year in reduced compliance costs. This enables them to expand, make investments and create more jobs.

The plan also includes making strategic investments in modern infrastructure. In an increasingly competitive global economy, well-maintained and modern infrastructure helps to attract investment and lower business and manufacturing costs. These infrastructure investments remain focused on the most critical areas, such as transportation, health care and education, and help support over 100,000 jobs annually across the province.

A highly skilled and adaptable workforce is critical to Ontario’s success. It will help us meet the challenges of rising global competition and technological change. We are providing even more opportunities for Ontario’s youth by introducing an Ontario Youth Employment Fund as part of the Youth Jobs Strategy.

The new government is also working to promote entrepreneurship and innovation. Ontario’s continued prosperity depends on its ability to transform ideas into innovative goods and services for global markets.

We are also focused on helping Ontario companies go global. Our export-based economy is well positioned to take advantage of emerging global opportunities. We are going to work with business to promote Ontario’s many export industry strengths and expand market access beyond Ontario’s borders to other provinces, the United States and into emerging markets. This will lead to increased competitiveness and productivity benefits.

Finally, we are going to continue to support our vibrant and strong communities across the province. We will continue to work with municipalities and local industries to overcome their unique challenges, while helping them take advantage of new opportunities for jobs and growth.

In 2012–13, we had a lower deficit and net debt-to-GDP is almost two percentage points lower than the 2012 Budget forecast. This marks the fourth year in a row that we have reported a deficit lower than forecast — making us the only government in Canada to achieve this level of success. These results are due to our focus on deficit elimination by 2017–18, a commitment that is reinforced by our goal of reducing net debt-to-GDP to the pre-recession level of 27 per cent once the budget is balanced.

Our plan for eliminating the deficit is to manage spending effectively but also includes strategic investments to create jobs and grow the economy. Growth in program spending was less than one per cent for the second consecutive year. In fact, program spending in 2012–13 declined for the first time in a decade. Once again, ministries, including Health and Education, contained their growth in spending and most managed well below their 2012–13 budget.

In the years ahead we are taking further action. We will move forward with our plan to transform public services by changing the way programs and services are delivered to give Ontarians better value for their money. We will further integrate recommendations from the Commission on the Reform of Ontario’s Public Services (the Commission) into our plans by continuing to move forward with 60 per cent of the recommendations this year.

Going forward, these and other actions will help us control the rate of growth in program spending in a way that is fair and balanced, while also ensuring the integrity of provincial revenues to fund public services and infrastructure.

Achieving these results will require some difficult choices. Ontario already has the lowest per capita spending on public services among the provinces. Across-the-board cuts are a simplistic tool that does not work; the Commission also advised against across-the-board cuts. This approach would actually hurt public services and undermine programs that are providing high-quality services to the public such as health care and education. Instead, we will continue to carefully review spending to determine which programs should be enhanced or reduced, while transforming public services to increase efficiencies and improve outcomes.

Our government is taking strong action now. And in the years to come, controlling spending growth will take the same, ongoing effort. Through a balanced approach we will continue to strategically invest in key public services such as health care and education, and focus on creating jobs while at the same time continue to reduce the deficit.

/s/ Charles Sousa

The Honourable Charles Sousa

Minister of Finance

INTRODUCTION

This Annual Report presents Ontario’s financial results, activities and position for the year ending March 31, 2013. The Annual Report is a key element of the Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario and central to demonstrating the Province’s transparency and accountability for financial resources.

This report compares the Province’s actual financial results for the 2012–13 fiscal year to the Budget plan presented in the fiscal update of April 25, 2012. It also outlines trends in a number of key financial indicators over the past several years. By providing comparisons and historical trends, the Financial Statement Discussion and Analysis contained in this Annual Report helps users of the financial statements to understand the impact of economic conditions and other factors on government finances for the year and over time. This information supports the government’s commitment to accountability and transparency in financial reporting.

Producing the Public Accounts of Ontario, including the three supplementary volumes and this Annual Report, requires teamwork and collaboration on the part of many staff members across the provincial government and Ontario’s public sector. In addition, the Office of the Auditor General plays a critical role in auditing and reporting on the Province’s financial statements. I would like to thank everyone who was involved in preparing the 2012–13 Public Accounts for their essential and valuable contributions.

We welcome your comments on the Public Accounts. Please share your thoughts by email at annualreport@ontario.ca, or by writing to the Office of the Provincial Controller, Re: Annual Report, Ontario Ministry of Finance, Second Floor, Frost Building South, 7 Queen’s Park Crescent, Toronto, ON M7A 1Y7.

/s/ Murray Lindo

Murray Lindo, CMA

Assistant Deputy Minister and Provincial Controller

Ontario Ministry of Finance

GUIDE TO THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS

The Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario comprise this Annual Report and three supporting volumes.

Annual Report

The Annual Report includes a Financial Statement Discussion and Analysis section that examines the Province’s financial results and other information. It also contains the Consolidated Financial Statements, which are made up of several documents and schedules:

|

|

●

|

The Auditor General’s Report expresses the opinion of the Auditor General as to whether the statements fairly report the activities of the government in accordance with Canadian public sector accounting standards.

|

|

|

●

|

The Consolidated Statement of Operations reports the annual surplus or deficit from operations in the period. It shows government revenue against the cost of providing programs and services and financing debt. The difference is the annual surplus or deficit. The statement also provides a comparison to the Budget plan presented in the fiscal update of April 25, 2012, which is referred to in this Annual Report as the Budget plan.

|

|

|

●

|

The Consolidated Statement of Financial Position shows the assets of the Province, which are classified as financial or non-financial, against its obligations. The Province’s net debt consists of its obligations less its financial assets. The Province’s accumulated deficit is its net debt less the value of its non-financial assets.

|

|

|

●

|

The Consolidated Statement of Change in Net Debt shows the impact of financing the annual deficit and investments in capital assets. As well, this statement reflects the annual change in the fair value of the Ontario Nuclear Funds Agreement (ONFA) investments.

|

|

|

●

|

The Consolidated Statement of Change in Accumulated Deficit shows the impact of the annual deficit and unrealized gains and losses due to changes in the fair value of the ONFA investments.

|

|

|

●

|

The Consolidated Statement of Cash Flow shows the sources and uses of cash over the period. Sources of cash include taxation and other revenues, increases in debt and decreases in financial investments, while uses of cash include operating expenses, investments in infrastructure and other assets. The Statement shows the impact of all these activities on the Province’s holdings of cash and cash equivalents over the year.

|

|

|

●

|

Notes and schedules provide further information on the items in the various statements and form an integral part of the Consolidated Financial Statements. The notes also include a summary of the significant accounting policies that reflect the basis on which the Province’s financial statements are prepared, as well as upcoming changes to accounting standards.

|

Supporting Volumes

Volume 1 contains ministry statements and detailed schedules of debt and other items. The ministry statements, which are presented on the accrual basis of accounting, compare the amounts that were appropriated by the Legislative Assembly to actual expenses incurred. The ministry statements include amounts appropriated to fund some provincial organizations, including hospitals, school boards and colleges. The results of all provincial organizations in the government reporting entity are consolidated with those of the Province to produce the Consolidated Financial Statements, following the methodology described in Note 1 to the statements.

Volume 2 contains the individual financial statements of significant provincial corporations, boards and commissions that are part of the government’s reporting entity, and other miscellaneous financial statements.

Volume 3 contains detailed schedules of ministry payments.

STATEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY

The Consolidated Financial Statements and Financial Statement Discussion and Analysis are prepared by the Government of Ontario in compliance with legislation and in accordance with the accounting principles for governments recommended by the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB) of the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants (CICA) and, where applicable, the recommendations of the Accounting Standards Board (AcSB) of the CICA.

The government accepts responsibility for the objectivity and integrity of these Consolidated Financial Statements and the Financial Statement Discussion and Analysis.

The government is also responsible for maintaining systems of financial management and internal control to provide reasonable assurance that transactions recorded in the Consolidated Financial Statements are within statutory authority, assets are properly safeguarded and reliable financial information is available for preparation of these Consolidated Financial Statements.

The Consolidated Financial Statements have been audited by the Auditor General of Ontario and his report appears on page 35 of this document.

/s/ Steve Orsini /s/ Murray Lindo

|

Steve Orsini

|

Murray Lindo, CMA

|

|

|

Deputy Minister

and Secretary of Treasury Board

|

Assistant Deputy Minister

and Provincial Controller

|

|

|

August 14, 2013

|

August 14, 2013

|

FINANCIAL STATEMENT DISCUSSION

AND ANALYSIS

OVERVIEW

|

2012–13 Actual results against 2012 Budget plan1 Table 1

($ Billions)

|

|||

|

2012

Budget2

|

2012–13

Actual

|

Variance

|

|

|

Revenue

|

112.6

|

113.4

|

0.8

|

|

Expense

|

|||

|

Programs

|

115.8

|

112.3

|

(3.5)

|

|

Interest on debt

|

10.6

|

10.3

|

(0.3)

|

|

Total Expense

|

126.4

|

122.6

|

(3.8)

|

|

Reserve

|

1.0

|

–

|

(1.0)

|

|

Annual Deficit

|

(14.8)

|

(9.2)

|

(5.6)

|

|

Notes:

1 Budget and related variance numbers may not add due to rounding.

2 As presented in the fiscal update of April 25, 2012.

|

|||

Ontario’s deficit for 2012–13 was $9.2 billion, a $5.6 billion improvement from the forecast outlined in the fiscal update of April 25, 2012. With this significant reduction, Ontario continues its strong track record in recent years of improving on its deficit projections through a combination of fiscal discipline and responsible management.

For the first year in more than a decade, total spending fell from the previous year. At $122.6 billion, total spending was 0.1 per cent lower than in 2011–12. Ontario remains committed to controlling the growth in spending while protecting key public services. This approach will help achieve the government’s goal of returning to fiscal balance by 2017–18 while continuing to build a prosperous and fair Ontario.

At $113.4 billion, revenues for 2012–13 were $0.8 billion above forecast, due largely to higher-than-expected income from government business enterprises and a one-time gain in taxation revenues, while spending on programs and interest on debt, at $122.6 billion, was $3.8 billion less than planned. Most ministries and program areas, including health care, spent less than planned in the Budget. The Province also used a $1.0 billion reserve built into the fiscal plan to further reduce the deficit.

Ontario’s economy continued to expand modestly in 2012–13, recording growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) of 1.5 per cent in 2012, lower than the projected 1.7 per cent. Solid gains in business investment and international exports as well as continued growth in household spending were the main contributors to growth in 2012.

The outlook for the global economy continues to be uncertain. Expectations for global economic growth have weakened, reflecting a slowdown in several key emerging market economies. Economic forecasts for the United States, a major export market for Ontario, have also been reduced. However, recently there are encouraging signs that U.S. growth is picking up. Ontario is addressing these and other challenges to its performance, including a high Canadian dollar and low productivity growth, with an economic plan intended to take advantage of opportunities for growth in the global economy.

This plan builds on leveraging such Ontario strengths as highly skilled workers and a commitment to modern infrastructure. These important elements of the plan underscore the need for continued strategic investments while maintaining an overall focus on fiscal balance.

The significant investments Ontario has already made in infrastructure and quality public services have helped to attract investment, ensure a strong workforce and improve quality of life. A Conference Board of Canada report, for example, estimates that Ontario’s recent and planned infrastructure investments boost Ontario’s GDP and lower the unemployment rate relative to where it would otherwise have been.

As a result of investments in education, health care and other key public services over the past several years:

|

|

●

|

Ontario continues to lead the country in achieving the best overall wait-times reductions of all provinces, and is transforming the system to ensure it remains sustainable;

|

|

|

●

|

Ontario’s students are ranked by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) among the best in the world, and perform above the Canadian average in all three areas of math, reading and science in national assessments; and

|

|

|

●

|

A commitment to a clean, modern and reliable electricity system has created a culture of conservation with measurable savings, significantly increased renewable energy supply and seen the shutdown of 11 of Ontario’s 19 coal-powered generating units.

|

Detailed performance results in each of these areas are presented starting on page 26.

ANALYSIS OF 2012–13 RESULTS

|

Details of 2012–13 Actual results against Budget plan1 Table 2

($ Billions)

|

||||

|

2012

Budget2

|

2012–13

Actual

|

Variance

|

||

|

Revenue

|

||||

|

Taxation

|

79.1

|

79.4

|

0.3

|

|

|

Government of Canada

|

21.8

|

21.7

|

(0.1)

|

|

|

Income from government business enterprises

|

4.1

|

4.5

|

0.4

|

|

|

Other non-tax revenue

|

7.6

|

7.8

|

0.2

|

|

|

Total Revenue

|

112.6

|

113.4

|

0.8

|

|

|

Expense

|

||||

|

Health

|

48.3

|

47.6

|

(0.8)

|

|

|

Education

|

23.9

|

21.7

|

(2.2)

|

|

|

Postsecondary and training

|

7.5

|

7.4

|

(0.1)

|

|

|

Children’s and social services

|

14.0

|

13.9

|

(0.1)

|

|

|

Justice

|

4.0

|

4.0

|

–

|

|

|

Other programs3

|

18.0

|

17.7

|

(0.3)

|

|

|

Total Program Expense

|

115.8

|

112.3

|

(3.5)

|

|

|

Interest on debt

|

10.6

|

10.3

|

(0.3)

|

|

|

Total Expense

|

126.4

|

122.6

|

(3.8)

|

|

|

Reserve

|

1.0

|

–

|

(1.0)

|

|

|

Annual Deficit

|

(14.8)

|

(9.2)

|

(5.6)

|

|

|

Notes:

1 Budget and related variance numbers may not add due to rounding.

2 As presented in the fiscal update of April 25, 2012.

3 Includes Teachers’ Pension Plan expense. In the Consolidated Financial Statements, this expense item appears under the Ministry of Education. Schedule 3 to the financial statements provides details.

|

||||

Through a combination of fiscal discipline and responsible management, Ontario performed $5.6 billion better than planned in 2012–13, going from an original deficit estimate of $14.8 billion in April 2012 to a final deficit of $9.2 billion. Much of the improvement arose from strong management of expenses, which came in $3.8 billion below plan. Higher-than-expected revenues contributed $0.8 billion to the improvement, and the government used a $1.0 billion reserve built into the plan to further reduce the expected deficit.

At the time of the 2012 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, released last October, the deficit projection had been revised to $14.4 billion to reflect higher revenue stemming from a higher 2011–12 tax base. By January, with the release of the 2012–13 Third Quarter Ontario Finances, the outlook had improved to $11.9 billion. This included additional expected gains on the revenue side, application of $0.5 billion of the reserve to deficit reduction, and a total expense outlook projected to be $1.2 billion lower than forecast. The lower expense projection largely reflected one-time savings in the Ministry of Education, which are explained in more detail in the section below entitled “Investments in services, programs and infrastructure” along with savings on interest on debt. These factors together reduced the deficit forecast by a further $2.5 billion.

The 2013 Budget, presented in May, provided interim projected results for 2012–13. With performance on track, the government applied the remaining $0.5 billion in the reserve to further reducing the deficit. The new projection of $9.8 billion, an improvement of $5.0 billion from the initial forecast, also included additional savings across ministries, further projected savings of interest expense as a result of the lower deficit forecast, and further upward revision of the revenue forecast.

The final deficit number for the year, at $9.2 billion, is $5.6 billion better than the initial forecast. The further improvement from interim reflects additional savings on the expense side, partially offset by downward revision of the revenue estimate. Page 31 sets out and discusses the variances between interim and actual results.

Revenue

Changes to taxation revenue are largely a reflection of economic activity. Ontario’s economy expanded by 1.5 per cent in 2012, as measured by growth in real GDP. This was below the 1.7 per cent growth projection used in developing the 2012 Budget plan.

Ontario and the rest of the global economy face continuing challenges. Ontario still relies heavily on the U.S. economy as a major export market and must address the issues of a high Canadian dollar and low productivity growth.

The government has already fundamentally restructured the tax system to improve Ontario’s business tax competitiveness and enhance Ontario’s advantages in sustaining long‐term economic growth and job creation.

Ontario’s plan for jobs and growth builds on strong economic fundamentals supported by government policy and investments in six key areas:

|

|

●

|

Competitive business climate — supporting a competitive tax system and effective regulation promotes new business investment for job creation and economic growth;

|

|

|

●

|

Modern infrastructure — investing in transit, roads, hospitals and schools is a key foundation for a productive economy;

|

|

|

●

|

Highly skilled workforce — investing in skills and education, as well as youth employment, ensures the people of this province can work and prosper;

|

|

|

●

|

Promoting entrepreneurship and innovation — strengthening Ontario’s ability to transform ideas into innovative goods and services for the global economy;

|

|

|

●

|

Going global — working with business to expand market access for goods and services beyond Ontario’s borders to other provinces, the United States and emerging economies; and

|

|

|

●

|

Vibrant and strong communities — helping all communities and regional economies benefit from job creation and economic growth.

|

These measures will enhance Ontario’s competitiveness and allow its businesses to take greater advantage of opportunities for growth in the global economy.

Ontario has already made considerable progress in recovering from the recession that began in 2008, the most serious global downturn since the 1930s. Real GDP is now 2.7 per cent above its pre-recession peak. Ontario has created more than 433,000 jobs since June 2009, recovering all of the jobs lost during the recession. The current level of employment is nearly 168,000 jobs above the high point before the recession.

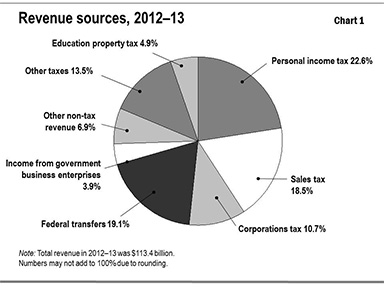

With the continuing recovery in Ontario, revenues have gradually expanded. Total revenue, at $113.4 billion, grew by 3.3 per cent in 2012–13 over the previous year.

Total revenue was $796 million higher than the level projected in the 2012 Budget plan, mainly as a result of higher-than-expected taxation revenues and income from government business enterprises.

Total taxation revenues were $295 million above forecast. A one-time boost to corporations tax related to tax assessments during 2012 for years before 2011 contributed to higher-than-projected revenues of $1.3 billion, but this was partly offset by lower results from most other sources of taxation. In particular, personal income tax revenues were $0.5 billion lower due to lower labour compensation growth and a one-time adjustment for an overestimate of the 2011–12 results.

Total non-tax revenues were up $501 million from the 2012 Budget plan.

The combined net income from investment in government business enterprises was $404 million higher than expected, reflecting stronger results across all four enterprises — the Liquor Control Board of Ontario, Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation, Ontario Power Generation Inc. and Hydro One Inc. The better-than-expected total reflected both lower expenses and stronger revenues in these businesses.

Other non-tax revenues were also up by $212 million, mainly from higher-than-expected recoveries of prior-year expenditures by ministries.

Transfers from the Government of Canada were $115 million lower than expected, partially offsetting the gains in total non-tax revenues. The decline was due mainly to lower infrastructure revenue and Canada Health Transfers. The decline in federal transfers was partially offset by a decrease in related spending.

Investments in services, programs and infrastructure

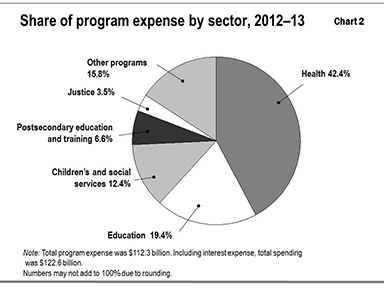

Continuing efforts to find savings and efficiencies were central to keeping program spending to $112.3 billion, as compared to the 2012 Budget forecast of $115.8 billion. Program spending decreased by 0.4 per cent from the previous year, falling from $112.7 billion, after an increase of only 0.9 per cent from 2010–11 to 2011–12.

Key variances between the Budget plan and actual results for the year include:

|

|

●

|

In the health care sector, a reduction in planned expense of $752 million, due mainly to lower-than-projected spending by hospitals through effective management of their budgets, lower hospital amortization expense than projected, savings in the Ontario Drug Benefit program, and lower-than-planned spending in various ministry programs, such as clinical education.

|

|

|

●

|

In the primary and secondary education sector, a decrease of $2.2 billion from plan due mainly to one-time savings of $1.3 billion from reducing liabilities carried by school boards for sick-day banking and retirement gratuities, and other lower-than-expected school board expense.

|

|

|

●

|

Postsecondary and training sector expense was $147 million lower, as lower-than-expected demand resulted in lower spending on financial assistance for students and on employment and training programs.

|

|

|

●

|

Children’s and social services sector expense was $126 million below plan, due mainly to lower-than-projected expenditures on the Ontario Child Benefit and the Children’s Activity Tax Credit, and lower-than-forecast Ontario Works caseloads.

|

|

|

●

|

Justice sector expense came in $85 million lower than planned, mainly because of lower-than-expected costs related to municipal policing, lower overtime costs and other internal efficiencies.

|

Expense for all other programs combined was lower than planned. Major decreases were attributable to:

|

|

●

|

Higher-than-forecast prices for agricultural commodities, reducing payments made under business risk management programs administered by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food and contributing to an overall decrease of $98 million in the ministry’s planned spending;

|

|

|

●

|

Actual electricity prices and consumption that differed from the assumptions used in forecasting the Ontario Clean Energy Benefit, lower-than-expected take-up of the Northern Ontario Energy Credit and savings in other areas that together resulted in a net reduction of $97 million in planned spending for the Ministry of Energy;

|

|

|

●

|

Internal efficiencies and lower-than-planned spending on a range of initiatives that reduced expense in the Ministry of Finance by $197 million from plan; and

|

|

|

●

|

A net reduction of $212 million in total expense for the Ministry of Infrastructure due mainly to a change in the accounting treatment of real estate assets under development.

|

Higher spending in some program areas, including funding the remediation of a contaminated site as required by federal legislation, revising media tax credit estimates for unprocessed applications and providing additional resources for fighting forest fires, partially offset these reductions.

The 2012 Budget plan included operating and capital contingency funds totalling $500 million to protect against unforeseen changes in expense. It also included a $500 million transition fund that could be drawn down if needed to help ministries manage costs associated with organizational changes. The portions of the contingency funds and transition fund that were unallocated by year-end were applied to further reducing the deficit.

The net impact of all changes in other programs was a reduction in spending of $258 million from plan.

Interest on debt for 2012–13 was $278 million lower than planned, reflecting mainly lower-than-forecast interest rates and lower deficits than expected for 2011–12 and 2012–13.

|

Infrastructure expenditures, 2012–131 Table 3

($ Billions)

|

|||

|

Sector

|

Investment

in Capital Assets2

|

Transfers

and Other3

|

Totals, 2012–13

Actual

|

|

Transportation and transit

|

4.7

|

0.5

|

5.2

|

|

Health

|

3.8

|

0.3

|

4.1

|

|

Education, postsecondary and training

|

2.0

|

0.2

|

2.2

|

|

Municipal and other

|

1.2

|

0.7

|

2.0

|

|

Totals

|

11.7

|

1.7

|

13.5

|

|

1 Numbers may not add due to rounding.

2 Includes adjustments for the net book value of assets disposed of during the year, as well as changes in valuation.

3 Mainly transfers for capital purposes to municipalities and universities and expenditures for capital repairs. Transfers for capital-related purposes and other infrastructure expenditures are recorded as expenses in the Province’s Consolidated Statement of Operations.

|

|||

Infrastructure spending, including third-party funding, was $13.5 billion, slightly below the $13.9 billion set out in the 2012 Budget. The change was due mainly to lower-than-forecast construction activity.

In an increasingly competitive global economy, well-maintained and modern infrastructure helps to attract investment and lower business and manufacturing costs. Infrastructure investments stimulate economic growth and job creation, support a cleaner environment, enhance the quality of life and contribute to the overall prosperity of Ontario.

In a recent report, the Conference Board of Canada found that each $100 million of public infrastructure investment in Ontario boosts GDP by $114 million. Among other findings, the report estimates that Ontario’s recent and planned infrastructure investments will add more than $1,000 to the average Ontarian’s annual income by 2014, and lower the unemployment rate by almost one percentage point relative to where it would otherwise have been.

Since 2003, Ontario has invested more than $85 billion in public infrastructure, supporting close to 100,000 jobs on average each year. Major investments include ReNew Ontario, short-term stimulus, and recent projects in such critical areas as transportation, health and education, consistent with the Province’s long-term infrastructure plan, Building Together.

Examples of recent and current infrastructure projects include:

|

|

●

|

Improving the flow of goods and people on Ontario’s highways by widening sections of Highway 11/17 between Thunder Bay and Nipigon and making improvements along Highway 417 in Ottawa, including bridge repair and replacement and widening sections of the highway.

|

|

|

●

|

Enhancing transit services by continuing to construct bus rapidways for use by Viva Bus Rapid Transit in York Region and constructing the Union Pearson Express, which will provide a new rail service linking Toronto’s Union Station to Pearson International Airport.

|

|

|

●

|

Investing in modern health infrastructure, such as the recently completed Bridgepoint Hospital in Toronto and 15 other major hospital projects under way across the province, including the New Oakville Hospital of Halton Healthcare Services.

|

|

|

●

|

Building better places to learn and supporting the rollout of full-day kindergarten across the province by providing more than $1.4 billion in capital funding since 2010 that is helping create close to 3,500 new kindergarten classrooms through additions and major retrofits.

|

|

|

●

|

Supporting the development of a skilled and innovative workforce by helping to fund the construction of major new facilities at colleges and universities, including Lakehead University Law School in Thunder Bay and Sir Sandford Fleming College’s Kawartha Trades and Technology Centre in Peterborough.

|

|

|

●

|

Working with the federal government to help address the infrastructure needs of Ontario’s communities, such as recent improvements to the Highway 8 Kitchener-Waterloo Expressway, which are part of a joint federal-provincial investment.

|

|

|

●

|

Strengthening municipal asset management planning through the Municipal Infrastructure Investment Initiative, by providing nearly $9 million to help municipalities prepare asset management plans.

|

Borrowing and financial position

Ontario’s total debt increased by $23.8 billion in 2012–13, net of refinancing, rising from $257.3 billion to $281.1 billion, with the increase applied mainly to financing the deficit and investing in infrastructure. Ontario successfully completed its annual borrowing program in 2012–13, despite continuing challenges in global financial markets, taking advantage of the historically low interest rate environment and strong demand for Ontario bonds.

Strong global investor demand for Canadian-dollar assets, the liquidity of Ontario benchmark bonds and continuing confidence in the Province allowed Ontario to borrow 72 per cent of its needs in the Canadian-dollar market in 2012–13. While down from 81 per cent in 2011–12, this is consistent with the target of at least 70 per cent set out in the 2012 Budget.

The following table summarizes how the Province used its net new financing in 2012–13:

|

Use of new financing by the Province, 2012–13 Table 4

($ Billions)

|

||

|

Operating deficit and other transactions1:

|

4.8

|

|

|

Cash invested in capital assets owned by the Province and its consolidated organizations, including hospitals, school boards and colleges2:

|

11.6

|

|

|

Increase in the Province’s cash and investments:

|

8.7

|

|

|

25.1

|

||

|

Less: Increase in other long-term financing3:

|

(1.3)

|

|

|

Net new financing

|

23.8

|

|

|

1 The Province’s operating deficit of $9.2 billion offset by a net $4.4 billion in changes to assets and liabilities that provided cash for operating purposes. See the Consolidated Statement of Cash Flow.

2 New investments of $11.7 billion less proceeds of $0.1 billion from the sale of tangible capital assets.

3 Including net increase in financing of capital projects through Alternative Financing and Procurement. These obligations reflect a claim on future government resources. See Note 5 to the Consolidated Financial Statements.

|

||

The Province’s net debt, which consists of its obligations less its financial resources, was $252.1 billion at March 31, 2013, up from $235.6 billion a year earlier. Net debt at year-end was lower than the $259.8 billion forecast in the April 25, 2012 fiscal update, owing largely to better-than-expected fiscal results. Financial resources, including cash, short-term and other investments, and accounts and loans receivable, amounted to $79.3 billion at year-end.

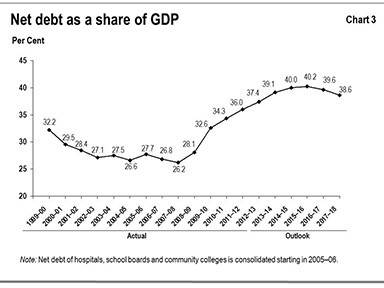

The ratio of net debt-to-GDP for 2012–13 was 37.4 per cent, an improvement from the 39.4 per cent projected for the year in the April 25, 2012 fiscal update. With the government’s plan to eliminate the deficit, increases in the ratio have moderated since the years immediately following the economic downturn that began in 2008. After eliminating the deficit by 2017–18, overall spending increases will be restricted to one per cent below GDP growth until the Province’s net debt-to-GDP ratio returns to the pre-recession level of 27 per cent.

Ontario’s borrowing program also provides a portion of the funds used to finance infrastructure projects, including transit, roads, hospitals and schools. These infrastructure investments steadily increase the level of assets available to provide public services. The net book value of these tangible capital assets was $85.0 billion at the end of the 2012–13 fiscal year, up from $77.2 billion a year earlier.

With Ontario on its way to a return to fiscal balance, the growth in debt continues to moderate. Although lower than forecast in the Budget plan, interest expense totalled $10.3 billion in 2012–13, up by $259 million from a year earlier. The government’s commitment to eliminating the deficit is key to helping control growth in interest expense.

Indicators of financial condition

The use of financial indicators helps the public and other readers of the Annual Report assess the financial health of the Province. The indicators’ levels and trends show the impacts of global economic events on the Province’s finances, as well as how the government is responding to these and other events.

|

Indicators of financial condition Table 5

|

|||

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

|

|

Net debt to revenues

|

200.2%

|

214.6%

|

222.4%

|

|

Interest expense to revenues

|

8.8%

|

9.2%

|

9.1%

|

|

Net debt-to-GDP

|

34.3%

|

36.0%

|

37.4%

|

|

Interest on debt to GDP

|

1.5%

|

1.5%

|

1.5%

|

|

Net debt per capita

|

$16,099

|

$17,497

|

$18,558

|

|

Federal transfers to total revenues

|

21.5%

|

19.4%

|

19.1%

|

|

Tangible capital assets per capita

|

$5,249

|

$5,732

|

$6,254

|

Such measures as net debt to revenues and interest expense to revenues show the relationships among government borrowings, the cost of those borrowings, and revenues. The ratio of net debt to revenues has increased as borrowings rose to cover the deficit and finance investments in infrastructure. Interest expense as a percentage of revenues declined slightly, with GDP increasing at a slightly faster rate than interest expense.

Net debt-to-GDP and interest expense to GDP both compare the government’s commitments to lenders to the province’s total economic output. Net debt-to-GDP has increased as the Province increased its borrowings to finance deficits in response to the global recession and provide stimulus funding to build infrastructure and protect jobs. However, with continued work to restrain growth in spending and trim annual deficits, the rate of growth of net debt has slowed, dampening growth in the ratio of net debt-to-GDP. As Chart 3 indicates, the ratio of net debt-to-GDP is expected to peak in 2015–16 and then begin declining. The ratio of interest on debt to GDP has been relatively stable for the past three years, showing that interest paid to lenders has grown at roughly the same rate as the Ontario economy.

The ratio of federal transfers to total revenues decreased to 19.1 per cent in 2012–13 from 19.4 per cent a year earlier. Federal transfers increased slightly in 2012–13 from the previous year, but revenue as a whole grew more strongly.

Tangible capital assets per capita provides a measure of how much the Province has invested on behalf of each resident in such important public assets as transit, roads, hospitals and schools. The steady increase in this ratio — from $5,249 in 2010–11, to $5,732 in 2011–12 and $6,254 in the year just ended — shows the extent to which people in Ontario are benefiting from the investments made to modernize, renew and update public infrastructure in recent years.

BALANCING THE BUDGET

Restraining growth in spending

The results of the fiscal year ended March 31, 2013 show that the Ontario government is acting on its plan to eliminate the deficit by 2017–18 in a way that is fiscally responsible, while strengthening the economy and building a more prosperous and fair Ontario.

To support deficit reduction, in February 2012 the Commission on the Reform of Ontario’s Public Services, led by Don Drummond, released a report on how to deliver the most effective and efficient public services possible and achieve sustainable fiscal balance. Over the 2012–13 fiscal year, the Ontario government began to move forward on more than half of the Commission’s 362 recommendations. In 2013–14, it is moving forward with a total of 60 per cent of the recommendations and is continuing to study the remainder.

Progress on implementing the Commission’s recommendations crosses many areas of service delivery and management, ranging from health care and tax compliance to environmental approvals and efficiencies in the justice system.

Ontario’s health care sector accounted for 42.4 per cent of the Province’s program spending in 2012–13. Transforming the sector to be sustainable while delivering quality services is a key priority in the government’s plan to eliminate the deficit.

Change is being shaped by Ontario’s Action Plan for Health Care, which the government released in January 2012. The Action Plan involves improving the quality of care based on the best available evidence and ensuring patients receive timely access to the most appropriate care in the most appropriate setting. The Action Plan and the Commission’s recommendations both aim to transform the health care sector to achieve quality care that is financially sustainable and better meets the needs of the people of Ontario. Significant achievements in the 2012–13 fiscal year included:

|

|

●

|

Continuing to implement a new patient- and activity-based hospital funding model to replace the existing lump-sum payments to hospitals, so that funding follows the patient and better reflects case complexity and volume of procedures;

|

|

|

●

|

Increasing investments in home care and community services to provide patients who do not need acute care, especially seniors, with quality care in the right setting and take pressure off hospital facilities;

|

|

|

●

|

Negotiating a new compensation agreement with the Ontario Medical Association that manages costs and works towards more effective health care through such mechanisms as e-consultations, expansion of telemedicine, and an evidence-based approach to ensuring procedures and tests are appropriate to the individual patient;

|

|

|

●

|

Expanding the scope of practice for pharmacists to administer flu vaccines and smoking cessation services; and

|

|

|

●

|

Developing a new income-tested deductible under the Ontario Drug Benefit program so that high-income seniors will pay more of their prescription drug costs.

|

In the areas of elementary, secondary and postsecondary education, the government is working to protect important gains, including improved student achievement, while ensuring fiscal sustainability. Key milestones in 2012–13 to implement the Commission’s recommendations included:

|

|

●

|

Implementing a different funding approach for successful secondary school credits beyond a 34-credit threshold;

|

|

|

●

|

Eliminating banked sick days and retirement gratuities, and making changes to post-retirement health benefits for elementary and secondary teachers;

|

|

|

●

|

In the postsecondary sector, working with institutions to develop formal agreements on their mandates as part of a strategy to support greater differentiation among institutions;

|

|

|

●

|

Harmonizing the range of scholarships, grants and other assistance programs across postsecondary institutions, and modernizing student aid programs; and

|

|

|

●

|

Supporting key projects by universities and employee groups to put single-employer pension plans on a more sustainable track.

|

In response to the Commission’s recommendations, in other sectors the government is also:

|

|

●

|

Reforming social assistance to improve employment supports, simplify asset and income rules, and increase program accountability;

|

|

|

●

|

Integrating employment and training services across government with Employment Ontario, and improving the collection of data on program uptake and outcomes;

|

|

|

●

|

Working to develop full-cost recovery models for environmental programs and services; and

|

|

|

●

|

In the justice sector, using civilians for administrative duties such as data entry, where possible, and streamlining operations by integrating programs and back-office functions.

|

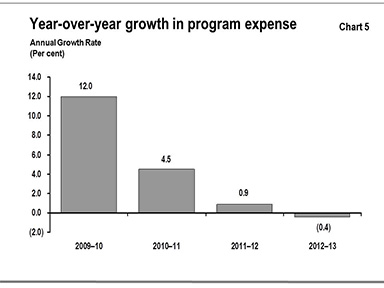

After 2009–10, annual increases in program spending declined sharply — from 12.0 per cent in the depth of the recession, when strong stimulus and supports were needed, to 4.5 per cent and then 0.9 per cent in 2011–12, and the past year saw the first decline in more than a decade.

The government of Ontario already spends less per resident delivering public services than any other province, and is working internally to achieve even greater cost effectiveness while continuing to offer quality, timely service. Reflecting measures to improve efficiency, Ontario’s per capita program spending in 2012–13 was $8,311, which was the lowest among the provinces.

The 2009 Budget announced measures to make the Ontario Public Service more efficient by reducing its size by five per cent or roughly 3,400 full-time equivalent staff over three years through attrition and other measures. The government achieved this reduction by March 31, 2012. It is well on its way to meeting a commitment to a further reduction of 1,500 full-time equivalent staff by March 31, 2014.

The Commission noted that the government’s pension expense had risen significantly in recent years and projected that, without action, it would continue to do so. Ontario acted in 2012–13 to mitigate this risk. After extensive consultation, it signed agreements with the four jointly sponsored pension plans consolidated in its financial statements. These agreements will freeze contribution rates at the levels already agreed to until the deficit is eliminated in 2017–18. During the freeze period, plans that experience new funding shortfalls will be required to reduce future benefits, subject to certain exceptions, instead of raising contribution rates.

The government’s pension expense is forecast to be a cumulative $6.5 billion lower by 2017–18 compared to the Commission’s forecast. This reduction can largely be attributed to the government’s successful efforts to constrain public‐sector wage growth and better‐than‐expected investment performance.

|

Pension expense, 2012–13 to 2017–181 Table 6

($ Billions)

|

||||||

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

|

|

Forecast, Commission on the Reform

of Ontario’s Public Services

|

3.1

|

3.7

|

3.6

|

3.7

|

4.0

|

4.2

|

|

Pension expense2

|

3.0

|

3.1

|

2.6

|

2.4

|

2.4

|

2.4

|

|

Difference

|

(0.1)

|

(0.6)

|

(1.0)

|

(1.4)

|

(1.6)

|

(1.8)

|

|

1 Numbers may not add due to rounding.

2 Actual for 2012–13, projected for other years.

|

||||||

The government has also provided temporary solvency funding relief to a number of single-employer pension plans, mainly in the university sector, in which the employer often bears a disproportionate share of contributions. The government remains committed to ensuring these plans move to equal cost-sharing for ongoing contributions within five years.

To find further savings and support measures to eliminate the deficit, Ontario is also:

|

|

●

|

Using the Alternative Financing and Procurement model to leverage private-sector resources and expertise to deliver projects on time and on budget. Infrastructure Ontario has applied the model to 83 capital projects for the Ontario government valued at about $38 billion, with an estimated $3 billion in value-for-money savings.

|

|

|

●

|

Establishing a working group to advise on the implementation of a pooled asset management entity for public sector pension plans.

|

|

|

●

|

Working with the federal government on enhanced compliance to address the underground economy and corporate tax avoidance and to support the integrity of Ontario’s tax system. In 2012–13, more than $200 million was realized through initiatives to reduce corporate tax avoidance.

|

|

|

●

|

Centralizing the collection of outstanding tax and non-tax accounts within the Ministry of Finance.

|

|

|

●

|

Working to increase value in such areas as Liquor Control Board of Ontario sales and gaming modernization while ensuring social responsibility.

|

Accountability and transparency in financial management and reporting

The government is accountable to the public for the appropriate use of taxpayer dollars and for clearly communicating the goals and results of its spending. Ontario continues to strengthen its accountability to the public, improve transparency in financial reporting, and ensure effective stewardship over government funds.

Publicly funded organizations, including provincial agencies, are accountable for delivering on the mandates assigned to them, while the ministries that oversee them must ensure that effective accountability tools are in place. The tools should both support financial and other reporting by agencies and identify when changes may be necessary to ensure that agency operations align with their mandates and achieve value for money. The government continues to improve the framework that supports these tools. During the year, it took action to enhance ministry reviews of their agencies and other organizations. These changes have placed greater focus on evaluating the entities’ financial results and internal controls, including identifying and mitigating risks and ensuring compliance with relevant government directives.

The government has enhanced the reporting and disclosure of salaries required under the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act, 1996. In June 2012, it amended the act to allow the Province to audit organizations subject to the act to help ensure full reporting compliance. In the fall of 2012, it extended the definition of salary to include per diem payments made to appointees of government bodies and other non‐profit organizations subject to the act. These changes have enhanced the transparency and accountability of public sector salary reporting.

Accounting standards determined by the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB) of the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants establish standards for the measurement and recording of the financial activities of governments and public sector organizations and the reporting of these to the public. To help ensure information is clear and understandable, consistency in measuring and presenting both planned and actual results is important. Alignment between fiscal plans and financial reporting is thus common among senior governments in Canada. Ontario, like other senior Canadian governments, continues to support the PSAB standards and to provide input to the standard‐setting process.

PSAB continues work on a project to review its accounting conceptual framework for the Canadian public sector. A sound conceptual framework is key to ensuring that PSAB’s standards continue to serve the public interest and reflect government accountability. Conversely, without a sound framework, governments might be forced to reconsider the basis upon which they report, in order to ensure clarity, accountability and consistency between planning and reporting. All Canadian senior governments, including Ontario, support efforts to develop a sound framework. Ontario expects that PSAB will incorporate the results of its conceptual framework review into its current standards and any future proposals. Additional discussion on the future direction of accounting standards is provided in the notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements, which form part of this Annual Report.

DELIVERING RESULTS

The government continues to focus on its key priorities — the public services like education and health care that people value and rely on, and that are helping to build prosperity, opportunity and a fair society. These services have benefited from significant public investments over the past several years, and this section outlines the measurable improvements that those investments have created. While Ontario is taking action to return to fiscal balance, preserving and building on those gains remains a priority.

Better access to health care, better value for money

Ontario has invested heavily over the past decade in improving the health care system. Performance measures and third-party evaluation show that, as a result, Ontario is the Canadian leader in such areas as reduced wait times for five priority medical procedures. Building on that foundation, Ontario is undertaking fundamental transformation of the health care sector to ensure that those gains are protected now and for future generations. Under the transformational plan laid out in the Action Plan for Health Care, the focus is on how the various parts of the health care system can work better together so that people stay healthier in the first place, family health care teams become the front door and navigators of the system, and services are delivered by the right provider at the right time and in the right place. At the same time, higher quality of care, better access to services and better value for investment will lead to improved patient and client satisfaction.

In the 2012–13 fiscal year, Ontario made significant progress on these goals:

|

|

●

|

To better integrate the delivery of care to high-needs patients — the five per cent of the population that accounts for two-thirds of health care costs — Ontario has to date created 25 Health Links, a new model that encourages greater collaboration among health care providers and could reduce unnecessary hospital visits and readmissions for patients with complex needs. The goal over time is to expand Health Links across the province.

|

|

|

●

|

Funding to hospitals is the largest area of health spending, so managing it is critical to controlling health care expenditures as a whole. The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care began phasing in Health System Funding Reform on April 1, 2012. This change will result in more efficient delivery of services and treatments through a transparent, patient-centred funding model that reimburses providers at an established rate, based on quality care for standard patient groups. At the same time, the growth in hospitals’ overall base operating funding was held to zero per cent in 2012–13.

|

|

|

●

|

Some 200 Family Health Teams now operate in Ontario, serving nearly three million patients — a number that is growing. This innovative primary health care model was launched in 2005 to provide broad-based services using interdisciplinary teams including health care professionals such as nurse practitioners, social workers and dietitians. Family Health Teams can see more patients, and physicians are freed up to focus more time on patients with complex health needs. About 718,000 people who previously did not have a family health care provider are now being served by a Family Health Team.

|

|

|

●

|

Nurse practitioner-led clinics are another innovative primary health care model. As of January 2013, 26 of these clinics were operational. This model, often used to provide primary care in previously underserved communities, is now caring for more than 32,900 patients, many of whom previously did not have a primary health care provider, and that number is climbing. Similar to the Family Health Team, it uses an interdisciplinary team to improve access to care.

|

|

|

●

|

As of January 2013, more than 189,000 Ontarians had been referred to a family physician or nurse practitioner through the Health Care Connect program, which helps people find a primary health care provider. Patients with the greatest need are referred first.

|

|

|

●

|

There were 25,480 physicians practising in Ontario in 2011, the most recent year for which data are available, compared to 24,875 in 2010.

|

|

|

●

|

In 2012, Ontario had 127,611 nurses compared with 126,573 in 2011. Ontario continues to be one of the few jurisdictions in the world to guarantee a full-time job opportunity to new nursing graduates. Since 2007, more than 14,300 new nursing graduates have received a full-time job opportunity through the Nursing Graduate Guarantee. Overall, the percentage of nurses working full time in Ontario was 66.6 per cent in 2012.

|

|

|

●

|

In 2012, Ontario was once again the national leader in reducing wait times for five priority health services, according to a report card issued by the Wait Time Alliance. In 2012–13, investments included $75.1 million in additional capacity in hip and knee revisions, general surgery, pediatric surgery, and MRI and CT scans. Ontario’s Wait Times Strategy is committed to increasing the number of procedures for targeted services; investing in new, more efficient technology such as MRI machines; standardizing best practices; and collecting and reporting wait-times data to allow better decision-making and increased accountability.

|

|

|

●

|

Ontario’s ground-breaking website, www.ontario.ca/waittimes, continues to publicly record and provide information on current hospital wait times for key health services across the province. Since implementation of the Wait Times Strategy, Ontarians are getting cataract surgeries 164 days earlier; hip and knee replacements 158 and 224 days earlier, respectively; key cardiac procedures up to 30 days earlier; cancer surgeries 33 days earlier; and general surgeries 23 days earlier. In addition, since 2008, patients with complex conditions are spending 30.4 per cent less time in emergency rooms and patients with minor, uncomplicated conditions are spending 17.6 per cent less time.

|

Keeping Ontario at the forefront of education and job creation

A well-educated workforce is a key pillar for job and growth. The overall skill and knowledge level of Ontario’s students must continue to rise to remain competitive in a global economy. At the same time, the achievement gap must be closed between students who excel and students who struggle because of personal, cultural or academic barriers. This is the foundation of a fair society in which everyone contributes to a higher quality of life.

Ontario continues to be recognized as a worldwide leader in education. This province has experienced nine consecutive years of improvement in student results — a feat that has earned international renown. A report released by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in March 2012, entitled Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education, noted that the Ontario government’s emphasis on elementary and secondary education has helped increase literacy and numeracy achievement, improve graduation rates and reduce the number of low-performing schools. This builds on previous OECD reports that ranked Ontario’s students among the best in the world.

The evidence is clear that the province’s students are now far better prepared to succeed:

|

|

●

|

As of September 2012, full-day kindergarten was being offered in roughly 1,700 Ontario schools, benefiting about 122,000 students or almost half of Ontario’s four- and five-year-olds. It marks the third year of the program, which gives Ontario’s youngest learners the best possible start and provides a solid foundation for future learning. About 184,000 students will benefit by September 2013, and full-day kindergarten will be available to all four- and five-year-olds by September 2014.

|

|

|

●

|

In 2011–12, the most recent year for which data are available, 70 per cent of students in Grades 3 and 6 were meeting or beating the provincial standard (a “B” grade) in reading, writing and math, up 16 percentage points from 54 per cent nine years ago. Over 50,000 more students in Grades 3, 6 and 9 were meeting or beating the provincial standard in reading, writing and math compared to 2002–03. Results for each division and school are available on the Education Quality and Accountability Office website at www.eqao.com.

|

|

|

●

|

Released in December 2012, the results of the 2011 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study show that Ontario’s Grade 4 students performed near the top in the world in reading achievement. Ontario’s students have sustained their high level in reading achievement since the previous evaluation in 2001 and have narrowed the gender achievement gap.

|

|

|

●

|

The Province’s goal of all primary classes in Ontario having 23 or fewer students was met in 2008–09 and has been maintained every year since. In 2003–04, only 64 per cent had 23 or fewer. Class sizes by school, school board and provincially are available at www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/cst/.

|

|

|

●

|

The number of students attending colleges or universities or learning a trade has increased by 220,000 since 2002–03, and there are 160,000 additional students enrolled at Ontario colleges and universities over the last 10 years, an increase that is greater than in any decade in Ontario’s history.

|

|

|

●

|

More than 350,000 students received Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) funding, including the 30% Off Ontario Tuition grant in 2012–13.

|

|

|

●

|

The percentage of working-age people in Ontario with postsecondary education rose to more than 65 per cent in 2012 from 56 per cent in 2002, while over the same period the graduation rate for university students increased to 81 per cent from 74 per cent, and for college students it rose to 65 per cent from 57 per cent.

|

A skilled workforce also depends on the ability to upgrade skills and learn while on the job. Employment Ontario investments of more than $1 billion in 2012–13 helped Ontarians access a wide range of employment and training services. Roughly one million Ontarians benefited, including employers who can use the Employment Ontario network to find workers; laid-off workers who benefit from skills training and other services; and workers, apprentices, newcomers and youth who get access to lifelong learning.

A clean, reliable electricity system

The government remains committed to a clean, reliable electricity system that focuses on conservation and new renewable energy sources, as well as such existing assets as Ontario’s strong hydroelectric network, to ensure the right balance of supply and demand. A major element of the government’s strategy is eliminating the emissions from coal-fired electricity generation.

|

|

●

|

As part of its commitment to a cleaner energy system, the Ontario government has shut down 11 of the province’s 19 coal-burning units since 2003. In September 2012, the Atikokan Generating Station closed to begin conversion from coal to biomass fuel. By the end of 2013, the Province will have shut down 17 of 19 coal units, completing the phase-out of 96 per cent of coal capacity. Eliminating coal-fired electricity generation will reduce annual carbon dioxide emissions by up to 30 megatonnes a year. To replace coal, Ontario is relying on a mix of conservation, refurbished nuclear, renewable energy and natural gas.

|

|

|

●

|

Since 2003, more than 12,000 megawatts (MW) of new and refurbished energy supply have come online, including a mix of cleaner gas-fired generation, nuclear power and renewable energy. This new supply includes more than 3,300 MW of renewable energy supply from wind, hydro, solar and bio-energy sources.

|

|

|

●

|

Ontario now has over 2,000 MW of wind power from more than 1,100 wind turbines online — enough to power 550,000 homes a year. In 2003, there were only 15 MW of wind power from 10 turbines. The province is also a leader in solar, with the most solar photovoltaic capacity online of any jurisdiction in Canada — over 750 MW, or enough to power more than 90,000 homes a year.

|

|

|

●

|

Ontario’s clean energy strategy has attracted significant renewable energy development, investments and economic opportunities. More than 30 companies are currently operating, or plan to build, solar and wind manufacturing facilities in Ontario. More than 31,000 clean energy jobs have been created, and municipalities across Ontario are currently building feed-in tariff projects, including Brockville, Kitchener, Lambton Shores, Markham, Waterloo and Welland.

|

|

|

●

|

The 10.2-kilometre Niagara Tunnel, the single biggest construction project in the Niagara region in almost six decades, became fully operational in early March 2013. The tunnel, which has increased the amount of water available to the Sir Adam Beck Generating Station, is producing enough clean, renewable hydro power to power about 160,000 homes a year. It is expected to operate for up to 100 years with little maintenance.

|

|

|

●

|

As a result of the government’s conservation and energy efficiency programs, as well as the efforts of families and business across the province, Ontario has saved more than 1,900 MW of electricity since 2005. Overall, in 2011, conservation programs in Ontario influenced 717 million kilowatt-hours of verified and sustained annual energy savings.

|

|

|

●

|

More than 4.7 million smart meters have been deployed across Ontario. These meters provide real-time readings of energy consumption, usually every hour, to utilities. Smart meters have also enabled time-of-use pricing, so that the price consumers pay for electricity now better reflects the cost of producing it. Over 4.4 million customers are currently on time-of-use pricing and more are coming on every day. Smart meters are also a key component in the transition to a smarter power grid and smart appliances, which will allow greater flexibility in shifting consumption away from the highest-demand periods, deferring the need for new generation and resulting in savings for ratepayers.

|

2012–13 INTERIM TO ACTUAL RESULTS

The Province provided interim estimates of results for 2012–13 in the 2013 Budget, tabled in May of this year. At that time, the deficit was estimated at $9.8 billion. The final deficit of $9.2 billion reported for the year represents an improvement of $0.6 billion from the interim estimate. Table 7 outlines the major variances from the earlier figure.

|

Comparison of 2012–13 Interim and Actual results Table 7

($ Billions )

|

||||

|

2012–13

Interim

|

2012–13

Actual

|

Variance

|

||

|

Revenue

|

||||

|

Taxation

|

80.3

|

79.4

|

(0.9)

|

|

|

Government of Canada

|

21.7

|

21.7

|

–

|

|

|

Income from government business enterprises

|

4.5

|

4.5

|

–

|

|

|

Other non-tax revenue

|

7.8

|

7.8

|

0.1

|

|

|

Total Revenue

|

114.2

|

113.4

|

(0.8)

|

|

|

Expense

|

||||

|

Programs

|

113.6

|

112.3

|

(1.4)

|

|

|

Interest on debt

|

10.4

|

10.3

|

(0.1)

|

|

|

Total Expense

|

124.0

|

122.6

|

(1.4)

|

|

|

Annual Deficit

|

(9.8)

|

(9.2)

|

(0.6)

|

|

|

Note: Interim numbers and related variances may not add due to rounding.

|

||||

Revenues were down slightly from the interim estimate. This was largely due to downward revision of taxation revenue estimates as additional information became available after the fiscal year-end.

The impact of the downward revision in revenue was more than offset by actual spending that was lower than estimated at interim reporting. This was largely due to lower spending in the education and health sectors than anticipated in the interim estimates. As well, the estimated expense for interest on debt was revised slightly downward.

CONSOLIDATED

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

|

Province of Ontario

Consolidated Statement of Operations

|

|||

|

($ Millions)

|

2012–13

Budget1

|

2012–13

Actual

|

2011–12

Actual

|

|

Revenues (Schedules 1 and 2)

|

|||

|

Personal Income Tax

|

26,085

|

25,574

|

24,548

|

|

Sales Tax

|

21,135

|

20,957

|

20,159

|

|

Corporations Tax

|

10,798

|

12,093

|

9,944

|

|

Education Property Tax

|

5,631

|

5,511

|

5,765

|

|

Employer Health Tax

|

5,149

|

5,137

|

5,092

|

|

Gasoline and Fuel Taxes

|

3,095

|

3,100

|

3,090

|

|

Ontario Health Premium

|

3,098

|

3,067

|

2,916

|

|

Other Taxes

|

4,132

|

3,979

|

4,084

|

|

Total Taxation

|

79,123

|

79,418

|

75,598

|

|

Transfers from Government of Canada

|

21,776

|

21,661

|

21,305

|

|

Income from Investment in Government Business Enterprises (Schedule 9)

|