0001894562false2023FY.321670.10.3216700018945622023-01-012023-12-3100018945622023-06-30iso4217:USD00018945622024-02-23xbrli:shares00018945622023-12-3100018945622022-12-310001894562us-gaap:NonrelatedPartyMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:NonrelatedPartyMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2022-12-31iso4217:USDxbrli:shares00018945622022-01-012022-12-310001894562us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:SeriesARedeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2021-12-310001894562prme:SeriesBNonredeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2021-12-310001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMember2021-12-310001894562us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2021-12-310001894562us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2021-12-310001894562us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2021-12-3100018945622021-12-310001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:SeriesARedeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:SeriesBNonredeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:SeriesARedeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2022-12-310001894562prme:SeriesBNonredeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:SeriesARedeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2023-12-310001894562prme:SeriesBNonredeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:AdditionalPaidInCapitalMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:AccumulatedOtherComprehensiveIncomeMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:RetainedEarningsMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:SubsequentEventMemberprme:PublicOfferingMember2024-02-012024-02-290001894562us-gaap:SubsequentEventMemberus-gaap:OverAllotmentOptionMember2024-02-012024-02-290001894562us-gaap:SubsequentEventMemberprme:PublicOfferingMember2024-02-290001894562us-gaap:SubsequentEventMemberprme:PublicOfferingMemberprme:WarrantPurchaseAgreementMemberMember2024-02-290001894562us-gaap:SubsequentEventMember2024-02-012024-02-2900018945622022-10-012022-10-31xbrli:pure0001894562prme:LaboratoryEquipmentMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FurnitureAndFixturesMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:ComputerEquipmentMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberprme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberprme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberprme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2023-12-310001894562prme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Member2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberus-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:MoneyMarketFundsMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Memberprme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Memberprme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Memberprme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2022-12-310001894562prme:USTreasuryBillsAndGovernmentSecuritiesMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel1Member2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel2Member2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FairValueInputsLevel3Member2022-12-31prme:security0001894562prme:LaboratoryEquipmentMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:LeaseholdImprovementsMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:LeaseholdImprovementsMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:FurnitureAndFixturesMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:ComputerEquipmentMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:ConstructionInProgressMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:ConstructionInProgressMember2022-12-31prme:vote0001894562prme:SalesAgreementMember2023-11-012023-11-300001894562prme:SeriesARedeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMember2019-09-300001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMember2022-10-122022-10-120001894562us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMemberprme:A2022StockOptionAndIncentivePlanMember2022-02-092022-02-090001894562us-gaap:SubsequentEventMemberprme:A2022EmployeeStockPurchasePlanMemberus-gaap:EmployeeStockMember2024-01-010001894562us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMemberprme:A2022StockOptionAndIncentivePlanAnd2019EquityIncentivePlanMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMemberprme:A2022StockOptionAndIncentivePlanMember2023-12-310001894562prme:A2022EmployeeStockPurchasePlanMemberus-gaap:EmployeeStockMember2022-02-090001894562prme:A2022EmployeeStockPurchasePlanMemberus-gaap:EmployeeStockMember2022-02-092022-02-090001894562prme:A2022EmployeeStockPurchasePlanMemberus-gaap:EmployeeStockMember2023-12-310001894562prme:A2022EmployeeStockPurchasePlanMemberus-gaap:EmployeeStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:A2022EmployeeStockPurchasePlanMemberus-gaap:EmployeeStockMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:TimeBasedStockOptionsMember2022-12-310001894562prme:TimeBasedStockOptionsMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:TimeBasedStockOptionsMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:TimeBasedStockOptionsMember2023-12-310001894562prme:PerformanceBasedStockOptionsMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:PerformanceBasedStockOptionsMember2022-12-310001894562prme:PerformanceBasedStockOptionsMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:PerformanceBasedStockOptionsMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2023-12-310001894562prme:RestrictedStockTimeBasedMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:RestrictedStockTimeBasedMember2022-12-310001894562prme:RestrictedStockTimeBasedMember2023-12-310001894562prme:RestrictedStockPerformanceBasedMember2022-12-310001894562prme:RestrictedStockPerformanceBasedMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:RestrictedStockPerformanceBasedMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:ResearchAndDevelopmentExpenseMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562us-gaap:GeneralAndAdministrativeExpenseMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:GeneralAndAdministrativeExpenseMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562us-gaap:DomesticCountryMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:DomesticCountryMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:StateAndLocalJurisdictionMember2023-12-310001894562us-gaap:StateAndLocalJurisdictionMember2022-12-310001894562prme:A21ErieStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2020-08-3100018945622023-11-3000018945622023-11-012023-11-300001894562prme:A38SidneyStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2021-07-012021-07-31prme:tradingDay0001894562prme:A38SidneyStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2021-07-310001894562prme:A64SidneyStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2021-07-012021-07-310001894562prme:A64SidneyStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2021-07-310001894562prme:A60FirstStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2021-11-300001894562prme:A60FirstStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2022-12-310001894562prme:A60FirstStreetCambridgeMassachusettsLeaseMember2023-12-310001894562prme:A480ArsenalStreetWatertownMassachusettsLeaseMember2022-05-310001894562prme:BroadInstituteIncMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementLicenseAgreementMember2019-09-012019-09-300001894562prme:BroadInstituteIncMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementLicenseAgreementMember2019-09-012019-09-300001894562prme:BroadInstituteIncMemberprme:SeriesARedeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementLicenseAgreementMember2021-04-012021-04-300001894562prme:BroadInstituteIncMemberprme:SeriesARedeemableConvertiblePreferredStockMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementLicenseAgreementMember2021-04-300001894562prme:BroadInstituteIncMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementLicenseAgreementMember2019-09-300001894562prme:BroadInstituteIncMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementLicenseAgreementMember2023-12-310001894562prme:BroadInstituteIncMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangement2022LicenseAgreementMember2022-12-012022-12-310001894562prme:CollaborativeAgreementPledgeMemberprme:BroadInstituteIncAndHarvardUniversityMember2021-02-012021-02-280001894562prme:CollaborativeAgreementPledgeMemberprme:BroadInstituteIncAndHarvardUniversityMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:CollaborativeAgreementPledgeMemberprme:BroadInstituteIncAndHarvardUniversityMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2019-09-012019-09-300001894562prme:NonSickleCellDiseaseMemberprme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2019-09-300001894562prme:SickleCellDiseaseMemberprme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2019-09-300001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2019-09-300001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2020-09-012020-09-300001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2020-10-012020-10-310001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberus-gaap:CommonStockMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2019-09-012019-09-300001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2021-01-012021-12-310001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:BeamTherapeuticsMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementRelatedPartyMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:CollaborativeArrangementOptionAndLicenseAgreementMemberprme:MyeloidTherapeuticsMember2021-12-012021-12-310001894562us-gaap:CommonStockMemberprme:CollaborativeArrangementOptionAndLicenseAgreementMemberprme:MyeloidTherapeuticsMember2021-12-012021-12-310001894562prme:MyeloidTherapeuticsMember2023-09-3000018945622023-10-012023-10-310001894562us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:EmployeeStockOptionMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562us-gaap:RestrictedStockMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:CoFounderShareholderMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMemberprme:ScientificConsultingMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:CoFounderShareholderMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMemberprme:ScientificConsultingMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:ReimbursementOfResearchAndDevelopmentExpensesMemberprme:MyeloidTherapeuticsMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2023-01-012023-12-310001894562prme:ReimbursementOfResearchAndDevelopmentExpensesMemberprme:MyeloidTherapeuticsMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2022-01-012022-12-310001894562prme:MyeloidTherapeuticsMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2023-12-310001894562prme:MyeloidTherapeuticsMemberus-gaap:RelatedPartyMember2022-12-310001894562us-gaap:SubsequentEventMemberprme:CysticFibrosisFoundationMemberus-gaap:CollaborativeArrangementTransactionWithPartyToCollaborativeArrangementMember2024-01-012024-01-31

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Washington, DC 20549

Form 10-K

(Mark One)

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

☑ | ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2023

OR

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

☐ | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 |

Commission File Number:

001-41536

PRIME MEDICINE, INC.

(Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |

Delaware | | 84-3097762 |

(State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) | | (IRS Employer Identification No.) |

21 Erie Street, Cambridge, MA | | 02139 |

(Address of principal executive offices) | | (Zip Code) |

Registrant’s telephone number, including area code:

(617) 564-0013

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | |

Title of Class | | Trading symbol(s) | | Name of Exchange on Which Registered |

| Common stock, par value $0.00001 per share | | PRME | | Nasdaq Global Market |

Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☐ No ☑

Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☑

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☑ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically every Interactive Data File required to be submitted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit such files). Yes ☑ No ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, a smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. See the definitions of “large accelerated filer,” “accelerated filer,” “smaller reporting company,” and "emerging growth company" in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act. | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| Large accelerated filer | ☐ | Accelerated filer | ☐ | Non-accelerated filer | ☑ | Smaller reporting company | ☑ | Emerging growth company | ☑ |

If an emerging growth company, indicate by check mark if the registrant has elected not to use the extended transition period for complying with any new or revised financial accounting standards provided pursuant to Section 13(a) of the Exchange Act. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has filed a report on and attestation to its management’s assessment of the effectiveness of its internal control over financial reporting under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (15 U.S.C. 7262(b)) by the registered public accounting firm that prepared or issued its audit report. ☐

If securities are registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act, indicate by check mark whether the financial statements of the registrant included in the filing reflect the correction of an error to previously issued financial statements. ☐

Indicate by check mark whether any of those error corrections are restatements that required a recovery analysis of incentive-based compensation received by any of the registrant’s executive officers during the relevant recovery period pursuant to §240.10D-1(b). ☐

Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is a shell company (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Act). Yes ☐ No ☑

The aggregate market value of the voting and non-voting common equity held by non-affiliates of the Registrant, based on the closing price of the shares of common stock on The Nasdaq Global Market on June 30, 2023, was $603,127,652

As of February 23, 2024, there were 119,939,247 shares of Common Stock, $0.00001 par value per share, outstanding.

DOCUMENTS INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE

Portions of the registrant’s definitive proxy statement for its 2024 Annual Meeting of Stockholders to be filed pursuant to Regulation 14A within 120 days of the end of the registrant’s fiscal year ended December 31, 2023 are incorporated by reference into Part III of this Annual Report on Form 10-K to the extent stated herein.

Table of contents

| | | | | | | | |

| | Page |

| Item 1. | | |

| Item 1A. | | |

| Item 1B. | | |

Item 1C. | | |

| Item 2. | | |

| Item 3. | | |

| Item 4. | | |

| | |

| | |

| Item 5. | | |

| Item 6. | | |

| Item 7. | | |

| Item 7A. | | |

| Item 8. | | |

| Item 9. | | |

| Item 9A. | | |

| Item 9B. | | |

| Item 9C. | | |

| | |

| | |

| Item 10. | | |

| Item 11. | | |

| Item 12. | | |

| Item 13. | | |

| Item 14. | | |

| | |

| | |

| Item 15. | | |

| Item 16. | | |

References to Prime Medicine

Throughout this Annual Report on Form 10-K, “Prime Medicine,” “the Company,” “we,” “us,” and “our,” and similar expressions, except where the context requires otherwise, refer to Prime Medicine, Inc. and its consolidated subsidiaries, and “our board of directors” refers to the board of directors of Prime Medicine, Inc.

From time to time we may use our website, our Twitter account (@PrimeMedicine) or our LinkedIn profile at https://www.linkedin.com/company/prime-medicine to distribute material information. Our financial and other material information is routinely posted to and accessible on the Investors section of our website, available at www.primemedicine.com. Investors are encouraged to review the Investors section of our website because we may post material information on that site that is not otherwise disseminated by us. Information that is contained in and can be accessed through our website or our social media is not incorporated into, and does not form a part of, this Annual Report on Form 10-K.We intend to apply for various trademarks that we use in connection with the operation of our business. This Annual Report on Form 10-K may also contain trademarks, service marks and trade names of third parties, which are the property of their respective owners. Our use or display of third parties’ trademarks, service marks, trade names or products in this Annual Report on Form 10-K is not intended to, and does not imply a relationship with, or endorsement or sponsorship by us. Solely for convenience, the trademarks, service marks and trade names referred to in this Annual Report on Form 10-K may appear without the ®, SM and ™ symbols, but the omission of such references is not intended to indicate, in any way, that we will not assert, to the fullest extent under applicable law, our rights or the right of the applicable owner of these trademarks, service marks and trade names.

Cautionary Note Regarding Forward-looking Information

This Annual Report on Form 10-K contains forward-looking statements which are made pursuant to the safe harbor provisions of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933, as amended, and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended (the “Exchange Act”). All statements, other than statements of historical facts, contained in this Annual Report on Form 10-K, including statements regarding our strategy, future operations, future financial position, future revenue, projected costs, prospects, plans, and objectives of management, are forward-looking statements. The words “anticipate,” “believe,” “envision,” “estimate,” “expect,” “goal,” “intend,” “may,” “plan,” “predict,” “project,” “strategy,” “target,” “potential,” “will,” “would,” “could,” “should,” “continue,” “contemplate,” “vision” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements, although not all forward-looking statements contain these identifying words.

Our business and our forward-looking statements in this Annual Report on Form 10-K involve substantial known and unknown risks and uncertainties, including, among other things, the risks and uncertainties inherent in our statements regarding:

•the initiation, timing, progress and results of our research and development programs, product candidates, preclinical studies and future clinical trials;

•our ability to demonstrate, and the timing of, preclinical proof-of-concept in vivo for multiple programs;

•our ability to advance any current and future product candidates that we may identify and successfully complete any clinical studies, including the manufacture of any such product candidates;

•our ability to pursue our areas of focus and any other additional programs we may advance;

•our ability to quickly leverage programs within our initial target indications and to progress additional programs to further develop our pipeline;

•the timing of our investigational new drug application submissions;

•the ability of our Prime Editing technology to address unmet medical needs in patients;

•the implementation of our strategic plans for our business, programs and technology;

•the scope and duration of protection we are able to establish and maintain for intellectual property rights covering our Prime Editing technology;

•developments related to our competitors and our industry;

•our ability to leverage the clinical, regulatory, and manufacturing advancements made by gene therapy and gene editing programs to accelerate our clinical trials and approval of product candidates;

•our ability to identify and enter into future license agreements and collaborations;

•developments related to our Prime Editing technology;

•regulatory developments in the United States and foreign countries;

•our ability to attract and retain key scientific and management personnel;

•our estimates of our expenses, capital requirements, needs for additional financing;

•the effect of unfavorable macroeconomic conditions or market volatility resulting from global economic conditions, and;

•other risks and uncertainties, including those listed under the caption “Risk Factors.”

We may not actually achieve the plans, intentions or expectations disclosed in our forward-looking statements, and you should not place undue reliance on our forward-looking statements. Actual results or events could differ materially from the plans, intentions and expectations disclosed in the forward-looking statements we make. We have included important factors in this Annual Report on Form 10-K, particularly in the "Summary Risk Factors" and “Risk Factors” sections, that could cause actual results or events to differ materially from the forward-looking

statements that we make. Our forward-looking statements do not reflect the potential impact of any future acquisitions, mergers, dispositions, joint ventures or investments we may make.

You should read this Annual Report on Form 10-K and the documents that we have filed as exhibits to this Annual Report on Form 10-K completely and with the understanding that our actual future results may be materially different from what we expect. We do not assume any obligation to update any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except as required by law.

This Annual Report on Form 10-K includes statistical and other industry and market data that we obtained from industry publications and research, surveys and studies conducted by third parties. All of the market data used in this Annual Report on Form 10-K involves a number of assumptions and limitations, and you are cautioned not to give undue weight to such data. We believe that the information from these industry publications, surveys and studies is reliable. The industry in which we operate is subject to a high degree of uncertainty and risk due to a variety of important factors, including those described in the sections titled “Summary Risk Factors” and “Risk Factors.”

Summary of the Material Risks Associated with Our Business

Our business is subject to a number of risks that if realized could materially affect our business, financial condition, results of operations, cash flows and access to liquidity. These risks are discussed more fully in the “Risk Factors” section of this Annual Report on Form 10-K. Our principal risks include the following:

•We have incurred significant losses since inception. We expect to incur losses for the foreseeable future and may never achieve or maintain profitability.

•We will need substantial additional funding. If we are unable to raise capital when needed, we will be forced to delay, reduce, eliminate or prioritize among our research and product development programs or future commercialization efforts.

•Gene editing, including platforms such as Prime Editing, is a relatively new technology that has not been extensively clinically validated for human therapeutic use. The approach we are taking to discover and develop novel therapeutics is unproven and may never lead to marketable products. We may incur unexpected costs or experience delays in completing, or ultimately be unable to complete, the development and commercialization of any product candidates.

•Clinical drug development involves a lengthy and expensive process, with an uncertain outcome. Because gene editing is novel and the regulatory landscape that will govern our current and future product candidates is uncertain and may change, we cannot predict the time and cost of obtaining regulatory approval, if we receive it at all, for our current and future product candidates.

•We may enter into collaborations with collaborators and strategic partners such as Beam Therapeutics or other third parties for the research, development, delivery, manufacturing and commercialization of Prime Editing technology and certain of the product candidates we may develop. If any such collaborations are not successful, we may not be able to capitalize on the market potential of our Prime Editing platform or product candidates.

•If conflicts arise between us and our collaborators or strategic partners, these parties may act in a manner adverse to us and could limit our ability to implement our strategies.

•If we are unable to obtain and maintain patent and other intellectual property protection for any product candidates we develop and for our Prime Editing technology, or if the scope of the patent and other intellectual property protection obtained is not sufficiently broad, third parties could develop and commercialize products and technology similar or identical to ours and our ability to successfully commercialize any product candidates we may develop and our Prime Editing technology may be adversely affected.

•Our rights to develop and commercialize our Prime Editing platform technology and product candidates are subject to the terms and conditions of licenses granted to us by others. If we fail to comply with our obligations in the agreements under which we license intellectual property rights from third parties or otherwise experience disruptions to our business relationships with our licensors, we could lose license rights that are important to our business.

•Our in-licensed issued patents and owned and in-licensed patent applications may not provide sufficient protection of our Prime Editing technologies and our future product candidates or result in any competitive advantage.

•The intellectual property landscape around the technologies we use or plan to use, including gene editing technology, is highly dynamic, and third parties may initiate legal proceedings alleging that we are infringing, misappropriating, or otherwise violating their intellectual property rights, the outcome of which would be uncertain and may prevent, delay or otherwise interfere with our product discovery and development efforts.

•We expect to expand our research, development, delivery, manufacturing, commercialization, regulatory and future sales and marketing capabilities over time, and as a result, we may encounter difficulties in managing our growth, which could disrupt our operations.

•The FDA, the EMA and the National Institutes of Health, or NIH, have demonstrated caution as well as concern regarding potential long term impacts in their regulation of gene therapy treatments, and ethical and legal concerns about gene therapy and genetic testing may result in additional regulations or restrictions on the

development and commercialization of any product candidates we may develop, which may be difficult to predict.

PART I

ITEM 1. Business

Overview

We are a biotechnology company committed to delivering a new class of differentiated one-time curative genetic therapies to address the widest spectrum of diseases. We are deploying Prime Editing technology, which we believe is a versatile, precise, and efficient gene editing technology.

In the past forty years, the genetic disorders causing many diseases have become more clear. Genetic mutations implicated in disease are diverse and can range from a single base error, which are known as point mutations, to errors that extend from two bases to several to thousands of bases, including multi-base insertions, deletions, duplications, or combinations thereof. Some mutations affect the coding regions of genes while others affect regulatory sequences that control the function of genes and can affect the function of larger biochemical and genetic pathways. Furthermore, as revealed by population-level genomic studies, natural genetic variations are known to protect against or to increase risk of disease. Given these insights, we believe that gene editing has the potential to treat and even cure many human diseases.

The field of genetic medicine has evolved tremendously over the last decade, with groundbreaking advances in gene therapy, cell therapy, ribonucleic acid, or RNA, therapy, and, more recently, gene editing. This past year saw the first CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing therapy (CASGEVY™) approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the FDA, for the treatment of sickle cell disease. These technologies represent significant advancements for genetic therapies but we believe Prime Editing is the only gene editing technology that, by itself, can edit, correct, insert and delete deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, sequences in any target tissue. We believe Prime Editing technology has transformative potential that could change the course of how many diseases is treated and overcome the challenges associated with current genetic therapies.

Prime Editing, originally developed by Dr. Liu and Dr. Anzalone and first described in a Nature publication in 2019, has potentially broad therapeutic applications. Prime Editing is the only gene editing technology that can edit, correct, insert and delete DNA sequences in any target tissue. It can correct mutations across many tissues, organs, and cell types, in dividing and non-dividing human cells. For example, Prime Editing technology has the ability to repair diverse mutations, including all types of point mutations, deletion mutations, insertion and duplication mutations and insertion-deletion mutations. Our analysis of more than 75,000 pathological, or disease-causing, mutations found in the National Center for Biotechnology Information ClinVar Database shows that those addressable by Prime Editing technology account for approximately 90 percent of genetic variants associated with disease. As such, we believe Prime Editing technology has the theoretical potential for repairing approximately 90 percent of known disease-causing mutations across many tissues, organs and cell types.

In addition, we believe our Prime Assisted Site-Specific Integrase Gene Editing, or PASSIGETM technology, may enable Prime Editing to insert gene-sized sequences precisely, potentially addressing large patient markets. PASSIGE uses Prime Editing to insert one or more recombinase recognition sequences at precisely chosen locations in the genome. In our preclinical studies, we have shown that a site-specific recombinase can locate the recombinase recognition sequence and carries out DNA recombination, resulting in the desired large DNA sequence insertion at the desired location in the genome. We believe that such a technology has the potential to precisely insert “gene-sized” pieces of DNA, at a predetermined and specific site in the genome. Taken together, Prime Editing’s versatile gene editing capabilities have the potential to unlock opportunities across thousands of potential indications.

Prime Editors also have the ability to create permanent modifications at their natural genomic location, resulting in durable edits that are passed on to daughter cells, and retain their native physiological control. Our next generation gene editing technology is designed to produce a wide variety of precise, predictable and efficient genetic outcomes at the targeted sequence, while minimizing unwanted bystander edits and off-target edits and avoiding double-stranded DNA breaks. Our Prime Editors are designed to make only the right edit at the right position within a gene.

If nuclease gene editing approaches are “scissors” for the genome, and base editors are “pencils,” erasing and rewriting a subset of single letters in the gene, then Prime Editing is a “word processor,” searching for the correct location and replacing or repairing a wide variety of target DNA.

To maximize the potential of our Prime Editing technology to provide one-time curative genetic therapies to the broadest set of diseases possible, we have built a diversified portfolio of investigational therapeutic programs organized around core areas of focus: hematology and immunology, liver, lung, ocular, and neuromuscular. We are advancing additional programs as potential partnership opportunities.

Recent highlights of the programs in our portfolio include the following:

•PM359, our first product candidate within our hematology area of focus, targets the p47phox variant of chronic granulomatous disease, or CGD, a serious life-threatening disease that presents in childhood. PM359 is comprised of autologous hematopoietic stem cells, or HSC, modified ex vivo using Prime Editors that have been designed to correct a high percentage of cells containing the disease-causing mutation. We plan to submit an investigational new drug, or IND, application with the FDA and/or clinical trial application, or CTA, in the first half of 2024. We believe Prime Editing is uniquely well-suited to address this form of CGD. We have completed our preliminary clinical trial design and selected global trial sites to maximize access to patients and expedite enrollment for PM359 clinical trials. In August 2023, we received rare pediatric drug designation, or RPDD, from the FDA for PM359. In addition, in January 2024, we received orphan drug designation, or ODD, from the FDA for PM359.

•Also in our hematology and immunology area of focus, in June 2023, we entered into a research collaboration with Cimeio Therapeutics, Inc., or Cimeio, to combine our Prime Editing platform and Cimeio’s Shielded Cell and Immunotherapy Pairs, or SCIP, platform to develop Prime Edited SCIP for genetic diseases, acute myeloid leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome. The overall goal of the research is to reduce the toxicity of conditioning regimens and introduce new therapeutic options to meaningfully expand the utility of HSC transplant and enable the in vivo selection of edited HSCs to potentially remove the need for transplantation entirely.

•We have demonstrated Prime Editing of cells preclinically at predicted therapeutically relevant levels for all of our leading programs, including Wilson’s Disease and Glycogen Storage Disease 1b, or GSD1b, in our liver area of focus, Retinitis Pigmentosa/Rhodopsin, or RHO, in our ocular area of focus, and Friedreich’s Ataxia in our neuromuscular area of focus. In 2023, we presented preclinical research across multiple programs, including proof-of-concept data from in vivo rodent and large animal studies. Specifically:

▪In October 2023, we reported preclinical data demonstrating the ability of liver-targeted Prime Editors to precisely correct with high efficiency one of the most prevalent disease-causing mutations of GSD1b in non-human primates, or NHPs, and mouse models. These data are the first Prime Editing data in NHPs, which we believe provide further proof-of-concept for our Prime Editing approach to potentially address a wide range of diseases.

▪We presented additional in vivo data in October 2023, demonstrating that Prime Editors can efficiently and precisely correct the predominant mutations that cause RHO associated autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. These data suggest that our proprietary dual adeno-associated virus, or AAV, platform can effectively deliver Prime Editors to the eye, with the potential to treat a range of retinal diseases.

•In our lung area of focus, we have expanded our efforts to develop Prime Editors for the treatment of Cystic Fibrosis, or CF, and in January 2024, we entered into a therapeutic development agreement with the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, or CFF, in which CFF agreed to provide Prime Medicine with up to $15 million to support development of hotspot editing and PASSIGE in CF, as well as our ongoing efforts to develop lipid nanoparticles, or LNPs, for delivery to the lung. Through hotspot editing, we aim to address multiple mutations at mutational hotspots using a small number of Prime Editors, potentially addressing a large percentage of individuals with CF with only a few Prime Editors. In parallel, using PASSIGE, we aim to address nearly all people with CF using a single superexon insertion strategy.

•In our chimeric antigen receptor T cell, or CAR-T, program, we presented preclinical data in December 2023, demonstrating that PASSIGE was greater than 80 percent efficient for non-viral, site-specific delivery of chimeric antigen receptor to primary human T-cells to generate CAR-T cells, and can be

multiplexed with Prime Editing at other target sites by non-viral one-step delivery with no loss of efficiency.

•Lastly, our comprehensive suite of assays used to identify potential off-target events has been expanded to include new, unbiased genome-wide tools. These analyses have continued to demonstrate minimal to no detectable off-target edits, chromosomal rearrangements or translocations. No off-target activity has been detected in any of our leading programs, including CGD, Wilson’s Disease, GSD1b, and RHO. We believe these preliminary analyses, across multiple editing programs, suggest a potentially best-in-class safety profile.

•We believe our Prime Editing programs are well-positioned to leverage the clinical, regulatory, and manufacturing advancements made to date across gene therapy, gene editing, and delivery modalities to accelerate progression to clinical trials and potential approval. To unlock the full potential of our Prime Editing technology across a wide range of therapeutic applications, we are pursuing a comprehensive suite of clinically validated delivery modalities in parallel. For a given tissue type, we intend to use the delivery modality with the most compelling biodistribution. Our initial programs rely on three distinct delivery methodologies: (a) electroporation for efficient delivery to blood cells and immune cells ex vivo; (b) lipid nanoparticle, or LNP, for non-viral in vivo delivery to the liver and potentially other organs in the future; and (c) AAV for viral delivery in vivo to the eye, ear, and the central nervous system, or CNS, and muscle.

•We believe the modularity of our platform means that we will be able to accelerate our ongoing efforts and enable rapid generation of new product candidates. We believe the core components, such as Prime Editors, delivery, manufacturing, off-target assays, clinical, and regulatory can be leveraged to drive acceleration, efficiency and execution of our pipeline.

Team

We began operations in the summer of 2020, after being co-founded by David Liu, Ph.D., a world-renowned leader in the field of gene editing, along with co-founder Andrew Anzalone, M.D., Ph.D., who conceived of and developed Prime Editing along with Dr. Liu and others. Dr. Anzalone joined as our Head of Platform Development with years of experience in Prime Editing. Keith Gottesdiener, M.D., joined in 2020 as our President and Chief Executive Officer. Drawn by the promise of Prime Editing’s ability to transform the field of gene editing, we have since assembled a diverse and growing team that has grown to approximately 230 as of December 31, 2023, with all key functional leadership and employees in place. Our research, technical, and clinical development teams consist of experts in gene editing and Prime Editing, computational biology, automation, data sciences, off-target biology, structural biology, RNA chemistry, protein engineering and molecular evolution, genetics, pharmacology, translational medicine, the manufacturing and delivery of genetic medicines, and clinical medicine and regulatory affairs.

Relationship with David Liu, Ph.D.

We benefit from a close working relationship with Dr. Liu. In addition to being a co-founder, Dr. Liu is the chair of our Scientific Advisory Board and a Board observer, meets regularly with Company representatives, and provides consulting services to us pursuant to a consulting agreement, or the Liu Consulting Agreement, related to gene editing and related technology for human therapeutic or prophylactic uses.

We have also licensed certain improvements to Prime Editing from Dr. Liu’s laboratory at Broad Institute and Dr. Liu has entered into an agreement with us pursuant to which he is obligated to assign to us any inventions with respect to the services he performs for us.

Our Strategy

Our goal is to transform the lives of patients with debilitating diseases through the application of our ground-breaking Prime Editing platform and technology. We are committed to developing safe and efficient therapeutics using Prime Editing approaches to address high unmet need across a broad spectrum of diseases, from rare genetic

diseases to severe, chronic and acute diseases, and ultimately to prevent disease before it occurs. Key components of our strategy are as follows:

•Deliver the broadest potential of Prime Editing in the service of patients. We believe our Prime Editing technology and capabilities represent the future of gene editing and could unlock broad applications in medicine and life sciences. As a result of our access to proprietary rights in groundbreaking technology and our continued investment to enhance this gene-editing approach, we have established a clear leadership position in Prime Editing. We have built a cross-disciplinary team consisting of dedicated, scientifically curious individuals and experts in Prime Editing and drug development who are passionate about our common goal of helping patients live longer, healthier lives.

•Deploy our technology to extend the application of one time potentially curative therapeutics to areas that we believe were not addressable before. To unlock the full potential of our Prime Editing technology across a wide range of therapeutic applications, we intend to advance multiple therapeutic programs into the clinic, initially focused on genetic diseases that we believe have a fast, direct path to treating patients, and those with high unmet need not currently addressable using other gene-editing approaches. Within our neuromuscular programs, for example, our initial focus on repeat expansion diseases is one of many potential areas of differentiation from other gene therapy and editing approaches, and was chosen to demonstrate where we believe Prime Editing has a unique genetic approach that could be applied to a large set of related diseases with high unmet need: the precise removal of pathogenic repeats at the natural gene location, returning the patient’s genome to wild-type genetics. Over time, we intend to push new and innovative technological developments to maximize Prime Editing’s versatile therapeutic potential, and unlock broad opportunities beyond the genetic diseases in our initial pipeline, potentially including immunological diseases, cancers, infectious diseases, and targeting genetic risk factors in common diseases.

•Advance our pipeline while simultaneously enhancing, validating and enabling our modular platform. We have established a diverse pipeline of investigational therapeutic programs organized around core areas of focus: hematology and immunology, liver, lung, ocular, and neuromuscular. In addition, we are advancing additional programs, such as CAR-T, as potential partnership opportunities. We have designed a modular platform within each core area, which we believe will accelerate our ongoing efforts and enable rapid generation of new product candidates. We believe the core components, such as Prime Editors, off-target assays, delivery, manufacturing, clinical, and regulatory can be leveraged to accelerate our pipeline to clinical trials and potential approval.

To unlock the full potential of our Prime Editing technology across our areas of focus, we are pursuing numerous clinically validated delivery modalities in parallel. For a given tissue type, we intend to use the delivery modality with the most compelling biodistribution and Prime Editing efficiency. We are currently focusing on three delivery modalities: (a) electroporation for delivery to blood cells and immune cells ex vivo; (b) LNP for non-viral in vivo delivery to the liver, lung and potentially other organs in the future; and (c) AAV for viral in vivo delivery to the eye, ear, and potentially the central nervous system, lung and muscle. Our goal is to develop highly modular delivery systems that allow us to rapidly develop new products targeting the same cells/tissues/organs by leveraging the approaches and data that precedes them.

•Continue to push the frontier of innovation in gene editing by optimizing and expanding our Prime Editing technology and capabilities. We plan to continue investing in our technology, team and intellectual property with a focus on reinforcing our leadership position and making fundamental progress towards better therapies for patients.

•Opportunistically evaluate synergistic and value-creating partnerships to maximize the broad potential of our platform. Our pipeline programs have been internally generated, and we retain worldwide development and commercialization rights to all of our programs. Given the broad potential of our technology, we intend business development to play an important role in building Prime Medicine, with the goal of accelerating our pipeline, bolstering our financial resources, and maximizing the potential of Prime Editing. Our overall partnership strategy includes: 1) partnering within our core areas to accelerate and globalize our current pipeline programs at the “right” stage of development; 2) outside our core areas,

entering into collaboration or license agreements for programs now that we would not otherwise pursue in the near term; and 3) accessing enabling innovations, such as delivery and manufacturing capabilities.

•Lead with our culture of integrity, ethics, innovation and respect in everything we do. We believe the potential of Prime Editing can only be achieved through the coordinated effort of our team and the support of our partners across academia and industry. To push the boundaries of where gene editing can go, we are committed to jointly defining and maintaining a culture that is transparent, develops trust, values integrity and ethics, puts patients first, is science and data driven, and encourages innovation.

Prime Editors: A Next Generation Gene Editing Technology

We are developing Prime Editors as a potentially new class of therapeutics with transformative potential to expand the application of curative precision genetic medicines to the broadest spectrum of diseases.

Genetic mutations implicated in disease are diverse and can range from errors of a single base, known as point mutations, to errors that extend beyond a single base, such as insertions, deletions, duplications, or combinations thereof. Other mutations can affect regulatory sequences that control the function of genes and can affect the function of larger biochemical and genetic pathways. Furthermore, natural genetic variations, revealed by population-level genomic studies, are known to protect against or to increase risk of disease. To maximize the impact of these genetic insights, we believe the ability to alter the human genome at the foundational level in a versatile, precise, efficient and broad manner may confer the greatest therapeutic impact on human disease.

Over the last decade, groundbreaking advances in gene therapy, cell therapy and RNA therapeutics have resulted in several approvals for genetic medicines that have transformed the treatment of certain severe genetic diseases and cancers as well as the prevention of infectious diseases, such as the mRNA vaccine for COVID-19. More recently, the first generation of CRISPR-Cas based gene editing approaches for gene disruption have demonstrated evidence of the ability to address diseases caused by genetic mutations, via either in vivo or ex vivo delivery to humans. In 2023, the first CRISPR/Cas9-based therapy (CASGEVY™) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of sickle cell disease, followed soon after by its approval for use in beta-thalassemia. In addition to first generation CRISPR approaches, several base editing investigational medicines, which enable targeted introduction of certain point mutations, have received IND clearance by the FDA, and clinical trials have begun.

Current Challenges for the Field of Genetic Medicines

Despite significant progress within gene therapy, cell therapy, and RNA therapeutics, there remain considerable limitations to current genetic medicine approaches that impede their ability to truly deliver on the promise of a curative, one-time therapy to the broadest set of patients.

Non-Targeted Gene Therapy

Non-targeted gene therapy includes using viral vectors, such as AAV, or retroviruses such as lentiviruses, to deliver new copies of genes, or transgenes, to cells. It also includes the broad field of mobile gene elements, such as retrotransposons and transposons. These approaches generally do not correct genes but insert new copies of genes or parts of genes into cells in a non-targeted manner. While having some important benefits, non-targeted gene therapy approaches have many key limitations. Certain non-integrating viral vectors, such as AAV, may have limited durability, and pre-existing immunity to the vectors could limit their use and ability to be re-dosed. For approaches that integrate genes, including transposons, retrotransposons, and retroviral vectors, gene integration may occur randomly at hundreds or thousands of sites in the human genome because it is not currently possible to direct their integration to a specific, desired genetic location. Randomly integrating approaches also carry the risk of insertional mutagenesis. In addition, non-targeted gene therapy approaches do not take advantage of normal endogenous regulation of gene expression, and instead lead to variable gene expression due to an inability to fine tune the vector copy number per cell.

Nuclease Gene Editing and Base Editing

First generation gene editing methods rely on a class of enzymes called nucleases, such as CRISPR, ZFNs, engineered meganucleases and TALENs, to create double-stranded breaks in DNA at a targeted location. The DNA

can then be repaired by one of two naturally occurring DNA repair pathways: (1) non-homologous end joining, or NHEJ, which patches the broken ends of the chromosomes back together and randomly creates indels, or insertions and deletions; or (2) homologous directed repair, or HDR, which can more precisely replace DNA at the target cut site with the delivery of a template of corrected DNA. However, given NHEJ is typically the dominant repair pathway in cells and due to the low efficiency of repair and complexity associated with HDR, most nuclease-based editing programs in the clinic have focused on an NHEJ-directed knock out approach to alter or silence gene expression.

Nuclease based gene editing approaches have several key limitations. First, there is a lack of predictability in genetic outcomes at the target site in NHEJ, such as randomly creating indels (efficient if the goal is to disrupt or knock out a gene). Using HDR to make corrections, replacements, or insertions has low percentage editing efficiency, does not have the ability to correct genes in non-dividing cells because HDR DNA repair machinery is only expressed in dividing cells, and requires a DNA template with the desired, corrected gene sequence to be delivered simultaneously, which increases complexity.

Nuclease editing also leads to unwanted DNA modifications associated with double-stranded breaks, including cell death response, genomic instability, off-target editing and the potential for oncogenesis. Finally, making multiple edits with nucleases that generate double-stranded breaks at multiple genomic locations has the potential to lead to unwanted large scale translocations and rearrangements, potentially limiting applicability to multiplex editing.

Base editing is an emerging gene editing technology that harnesses CRISPR-Cas9 to deliver a deaminase to a target DNA site, which can edit a single base efficiently. Base editing avoids double-stranded breaks and the deleterious effects associated with first generation nuclease editing, while enabling C-to-T or A-to-G base substitutions edits using either a Cytosine Base Editor, or CBE, or Adenine Base Editor, or ABE, respectively.

Base editing has several key limitations. Currently, base editing can reliably correct only four out of 12 possible single base mutations, and base editing cannot make or correct insertion or deletions, which limits the number of diseases base editing can address. Further, each base editor (CBE or ABE) has the ability to correct or introduce only a single point mutation at a specific location. Base editing also has been shown to make certain types of unwanted on-target by-products, called bystander edits, near the targeted site, e.g., modifying nearby bases which are not being targeted but fall within the editing window. Finally, base editing may have limited optionality for targeting mutations due to its smaller editing window.

Prime Editing: A Next Generation Gene Editing Approach

Prime Editing is a next generation gene editing approach that we believe can address the genetic cause of disease and potentially provide patients with long-lasting cures. Although Prime Editing is a developing technology and is not yet validated in clinical studies, it was first described in a Nature publication in December 2019 and has since been extensively validated in vitro and in animal studies, both by our company and in over 150 papers published in the primary scientific literature to date.

Advantages of our Prime Editing Platform

We believe Prime Editing is a versatile, precise, efficient and broad gene editing technology with the following key advantages:

Versatility: Deep and highly differentiated toolbox of editing capabilities to enable a wide variety of therapeutic applications

•Applicable to a wide range of target mutations or alterations of DNA, including all twelve types of single base pair corrections, as well the ability to insert and delete DNA sequences.

•Direct correction of DNA with no requirement for delivery of the corrected DNA sequence in most applications of Prime Editing.

•Greater optionality with respect to editing site availability than other approaches due to a larger editing window.

•Programmable, which means that both the specified target location in the genome and the directed type of edit can be easily modified by replacing the Prime Editing guide RNA, or pegRNA, element of a Prime Editor.

•Modular for targeting a broad set of mutations, meaning that by redesigning the pegRNA a new mutation can be targeted for correction.

•Multiple potential therapeutic applications, including but not limited to targeted gene correction, gene silencing or activation such as by altering the regulatory regions of genes, inserting or creating premature stop codons, or by modifying splicing sequences, hotspot region replacement, multiplex editing of several genes simultaneously, and wild-type variant modification to protect against or modify risk for a disease.

•Capable of inserting, deleting or inverting kilobase amounts of genomic DNA by combining Prime Editing with proprietary recombinase technology in an approach we call PASSIGE.

Precision: Highly specific and predictable gene editing

•Designed to specifically make only the directed type of Prime Edit at the desired target location.

•Avoidance of the potential negative impacts associated with double-stranded breaks, which results in minimal to potentially no unwanted on-target or off-target by-products and preservation of cell viability.

•Limited potential for bystander editing at the target site, a potential unwanted effect of base editing.

Efficiency: Durable gene edits with potential for superior therapeutic activity

•Single treatment resulting in permanent corrections of disease-causing mutations by restoring the targeted gene back to its wild-type sequence.

•Permanent, durable edits that persist in a cell and are passed along to daughter cells, creating potential for a life-long, “once and done” therapeutic outcome.

•Preservation of natural regulation and a normal number of copies of the gene in the cell by modification of genes in situ, or in their native genomic setting.

•Highly efficient, effecting therapeutically relevant levels of precise gene correction generally unachievable by nuclease-based methods.

Breadth: Able to address a wide range of diseases in multiple tissue types

•Applicability in a wide range of human cells, including both dividing and non-dividing human cells, a wide range of organs and cell types, as well as in a wide variety of other organisms, as well as including primary cells such as hepatocytes, hematopoietic stem cells and neurons.

•Potential ability to repair approximately 90 percent of all types of mutations known to cause genetically driven disease.

•Broad therapeutic potential extending beyond rare genetic diseases to also potentially include severe, chronic, and acute diseases. In addition to correcting disease-causing mutations, potential for gene modification to edit naturally occurring variations within genes known to protect against or modify risk for a disease.

Mechanism

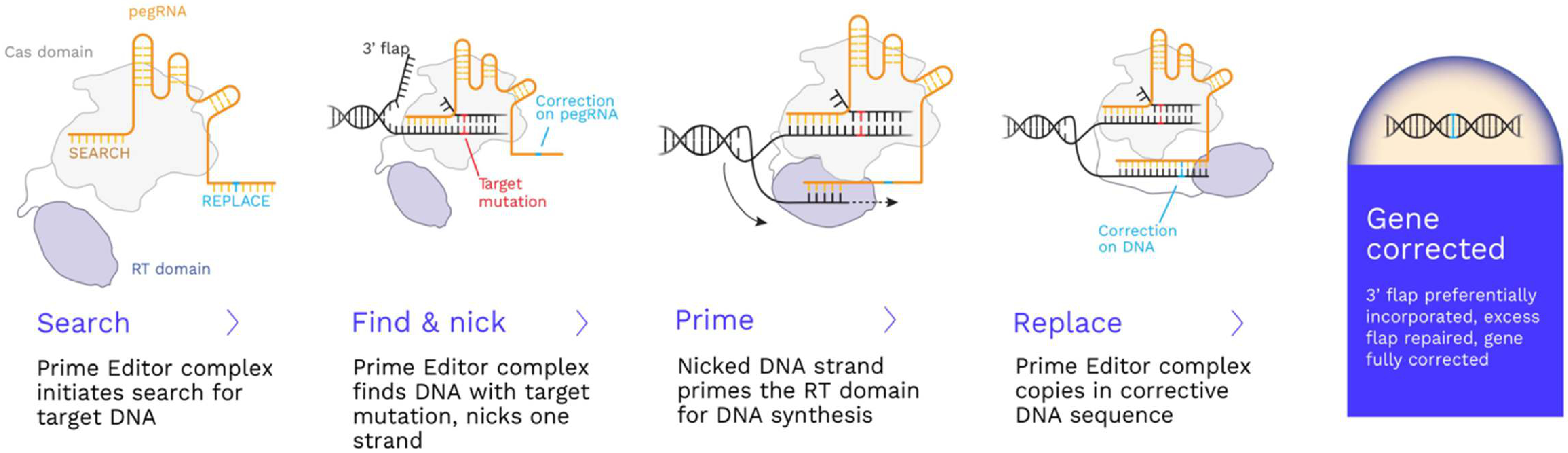

Prime Editors have at least two major components, a Prime Editor protein and a pegRNA. Our Prime Editor proteins contain two protein domains. The first domain is a programmable DNA binding domain, often a CRISPR-Cas domain, or Cas domain. Cas proteins enable targeting of specific DNA sequences, and they have been adapted and engineered to target desired genomic locations in human cells with high specificity. In Prime Editors, programmable DNA binding domains, such as Cas domains, for example Cas9 proteins, are modified such that they do not cause a double-stranded break in the DNA. The second protein domain of Prime Editors is a reverse transcriptase enzyme domain, or RT domain. Reverse transcriptases are DNA polymerase enzymes that write new DNA sequences by

copying from an RNA template. In Prime Editing, the RT domain copies the edited DNA sequence directly into the target genomic site where the edit is made.

The other main component in Prime Editing is the pegRNA. The pegRNA contains a search sequence, also known as a spacer, which provides a target genomic address for the Prime Editor. This enables the Prime Editor to specifically target a desired gene sequence. The pegRNA also contains a second sequence unique to Prime Editing, a replace sequence, or edit template, which provides a blueprint for the edit that will be made to the target DNA sequence.

As shown in the second panel in the figure below, our Prime Editor protein, exemplified using a Cas protein, and the pegRNA locate the DNA target site using the pegRNA’s search sequence. When the correct DNA target is found (referred to as “edit check 1,” as described below), the Prime Editor’s Cas domain cleaves, or nicks, one of the two DNA strands, creating a single-stranded 3’ flap. The other DNA strand remains intact and is not cleaved by the Prime Editor, thus avoiding the formation of double-stranded DNA breaks. Next, the 3’ flap binds to a region of the replace sequence in the pegRNA (“edit check 2”) and “primes” the DNA synthesis, which is shown in the third panel below. The Prime Editor’s RT domain copies the pegRNA’s replace sequence, directly writing the corrected DNA sequence into the gene, as shown in the fourth panel. After the corrected sequence is fully copied, cellular DNA repair preferentially incorporates the corrective 3’ flap (“edit check 3”) while removing the excess original DNA sequence. The complementary DNA strand is also corrected, using the Prime-Edited DNA strand as a template. Incorporation of the correction into the complementary DNA strand can be made more efficient by adding a nicking guide RNA, or ngRNA, where the Prime Editor also transiently nicks the complementary strand. The overall result is a target gene sequence that is corrected on both strands of DNA.

As highlighted above, there are three distinct steps in the Prime Editing pathway that require exact matches between the target DNA and pegRNA sequences. Thus, the process of Prime Editing efficiently institutes three “edit checks,” or three sequential steps where only if the match is exact does the next step occur. In addition to the lack of double-stranded DNA breaks, we believe that these “edit checks” are also important in helping to ensure that the right sequence in the genome is precisely edited in the desired manner, thereby minimizing both on- target and off-target mis-editing.

Illustration of Editing Mechanism by Prime Editor – No Double-Stranded DNA Breaks

Further Enhancing the Prime Editing Platform

Over the last four years since Prime Editing was first described, an increase in efficiency as well as an expansion in the scope of applications have been demonstrated and reported in multiple publications and abstracts as well as contributions from our team. The versatile nature of Prime Editing allows for the selection of the right tools for a specific gene edit from up to ten thousand potential choices to optimize for desired effects with high efficiency and precision at the targeted site, while minimizing off-target edits at more distant chromosomal sites.

Multiple enhancements to our Prime Editing platform, including engineered pegRNAs, enhanced Prime Editors, and DNA mismatch repair modulation, provide us with a versatile toolbox for applying Prime Editing to a wide range of diseases. In addition, our focus on high-throughput screening and machine learning are allowing us to grow our internal technical expertise for Prime Editing optimization and are being used to develop Prime Editors that are both

more efficient and more precise. Finally, we are broadening the types of edits that we can make by incorporating recent innovations in Prime Editing, including dual-flap Prime Editing, long-flap Prime Editing, and PASSIGE.

Dual-flap Prime Editing and long-flap Prime Editing

We have in-licensed certain dual-flap Prime Editing technology developed by David Liu’s laboratory at Broad Institute, and expanded and improved on its uses. Compared to traditional Prime Editing, dual-flap Prime Editing uses two Prime Editors instead of one. In different places on a target gene, each of the Prime Editors creates a nick in the DNA and creates a flap; the two flaps are often designed to bind tightly to each other. This results in the looping out of the DNA between the Prime Editors, with replacement by new DNA. Dual-flap Prime Editing is designed to achieve efficient editing of a broader range of edit types, including the precise replacement or insertion of DNA sequences that are a hundred bases or more in length with potentially higher efficiency than standard Prime Editing. In addition, dual-flap Prime Editing can precisely delete up to thousands of bases of DNA, as shown in the data for repeat expansion diseases (see below in Portfolio section). In addition to its high efficiency, it achieves the same level of precision, and we believe it results in minimal off-target editing, as shown in preclinical studies, similar to the more standard forms of Prime Editing. Dual-flap Prime Editing could be used to delete expanded repeat sequences like those that occur in repeat expansion diseases, to replace mutation hotspots with corrected sequences, or to insert sequences at safe harbor or other locations in the genome, as can be applied to our PASSIGE approach.

Additionally, we have developed a long-flap Prime Editing approach that, compared to standard Prime Editing, is designed to more efficiently insert or replace larger stretches of DNA that are a hundred bases or more in length, while also enabling precise deletions of up to thousands of base pairs. Long-flap Prime Editing can be applied for similar applications as dual-flap Prime Editing, including editing of hotspot regions in DNA, insertions of recombinase sites for PASSIGE, and the excision of expanded repeats. Together, dual-flap Prime Editing and long-flap Prime Editing broaden the capabilities of our Prime Editing platform.

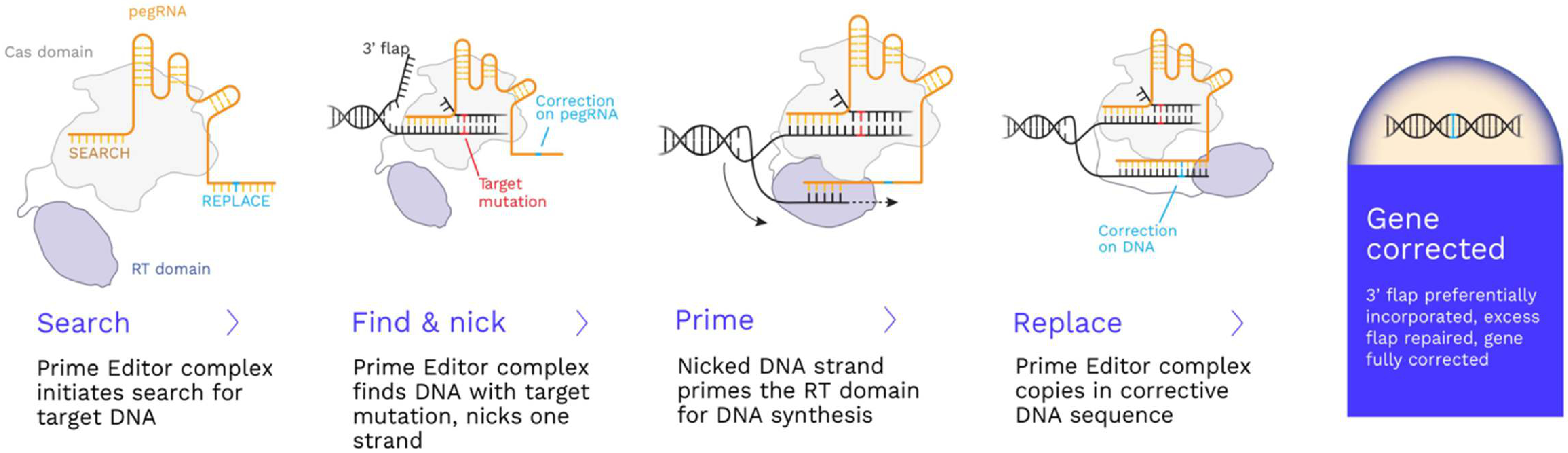

PASSIGE – Precise introduction of gene-sized pieces of DNA into the genome

We have in-licensed from the Broad Institute and are developing a technology that allows us to expand our gene editing toolbox to include programmable insertion, deletion, or inversion of thousands of bases of DNA. By combining Prime Editing with an integrase or site-specific recombinase enzyme, we can harness the precision of Prime Editing with the ability to introduce large gene-sized cargo into the genome as a potential one-time therapy for patients. This proprietary approach expands the versatility of Prime Editing and we believe broadens the range of permanent genomic edits that Prime Editing can make to encompass the ability to insert entire genes precisely into a patient’s genome to treat disease. Although site-specific recombinases have been used as biology research tools to perform insertions, deletions or inversions of large pieces of DNA in the genome, their use in therapeutic applications has been limited by the extremely challenging task of engineering site-specific recombinases to be programmable or to target specific sequences in a gene or the genome. PASSIGE technology complements dual-flap Prime Editing, which is able to delete large pieces of DNA up to many kilobases in size, but which currently can only precisely insert a smaller piece of DNA. Therefore, in circumstances where a larger modification is required, this programmable technique can be used to insert or invert multi-kilobase-sized pieces of DNA.

PASSIGE leverages the programmability of Prime Editing to insert recombinase recognition sequences at precisely chosen targeted locations in the genome, as shown in the figure below. A site-specific recombinase, either fused to the Prime Editor or transiently delivered as a separate enzyme into target cells, locates the recognition sequence or sequences and carries out DNA recombination at those recognition sequences, resulting in the desired large DNA sequence edit at the desired location in the genome. We believe that such a technology has the potential to precisely insert “gene-sized” pieces of DNA at a predetermined and specific site in the genome.

As shown in the figure below, PASSIGE may be used to insert DNA that contains a therapeutic gene, potentially such as a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, or the open reading frame of any other gene. Alternatively, using multiplex Prime Editing, two recombinase DNA target sequences can be inserted so that site-specific recombinases can replace, delete, or invert the intervening DNA sequences. These editing capabilities enable therapeutic opportunities to potentially treat genetic mutations occurring across a large region of DNA sequences within a single gene, and enable therapeutic opportunities to engineer cell therapies to treat disease.

PASSIGE™ – Extending Prime Editing to insert gene sized sequences precisely in the genome

Translating Prime Editors into Product Candidates - Multiple Modalities for Prime Editors

The optimal design and efficient generation of our Prime Editors are fundamental for the development of our pipeline. We have established capabilities to design and optimize our Prime Editors, and to design and develop the components needed for LNPs, vector genomes, Prime Editing of ex vivo cells, as well as to develop the manufacturing processes and analytical assays to ensure robust, scalable production of quality intermediates and products to support our programs. Many of these workflows are automated to allow rapid machine learning and/or artificial intelligence-based data analysis, correlation, visualization, and iterative optimization and innovation.

For each program in our pipeline, we determine the best option for delivering the Prime Editor and select the delivery technology with the most compelling biodistribution for a given tissue type. Our initial programs rely on three distinct delivery modalities: (a) electroporation for delivery to blood cells and immune cells ex vivo; (b) LNPs, for non-viral in vivo delivery to the liver, lung and potentially other organs in the future; and (c) AAVs for viral in vivo delivery to the eye and ear, and potentially the central nervous system, lung and muscle. A key feature of Prime Editing and associated delivery methods is the modularity of the technology platforms. Once the first program for each delivery platform is established, the design algorithms, workflows, non-clinical and CMC data, as well as the manufacturing process and majority of assays can be leveraged and applied to the next program which differs only in the pegRNA.

We believe these delivery technologies are foundational to successfully advancing our pipeline programs to the clinic and we are strategically developing our delivery platforms and generating data to accelerate our pipeline progress. Moreover, we continue to assess the many advancements in novel and experimental delivery approaches that are being made in the cell and gene therapy field and intend to license innovative delivery technologies that prove to provide a breakthrough.

We are designing Prime Editing product candidates to provide a “once and done” treatment. Our multi-pronged approach to enable our portfolio includes the following:

•pegRNA Design, High Throughput Screening and Synthesis: An important element of our capability is leveraging high throughput automated screening and design algorithms to identify optimal pegRNA sequences. The data is also used to develop proprietary machine learning algorithms for pegRNA activity prediction. Internal chemistry capabilities facilitate high-throughput optimization and manufacture of oligonucleotides for in vivo studies. We have established internal high-throughput pegRNA synthesis, pegRNA modifications with structure-activity-relationship to improve drug candidate properties, and pegRNA process chemistry.

•Optimization of Prime Editing proteins and recombinase proteins: We have developed internal protein engineering capabilities to optimize the Prime Editor proteins and recombinase proteins (for PASSIGE) for human therapeutic use, and have developed internal mRNA design and optimization, enzymatic chemistry, and process development capabilities to enhance drug candidate properties and characterize the mRNA for efficient, tolerable, and consistent delivery and translation of the Prime Editor protein.

•Prime Editing Specificity and Assays: A robust and unbiased evaluation of all potential off-target activities is a critical element of our efforts. Our approach to minimizing off-target editing is to start by screening for Prime Editor candidates with very low off-target activity. We then use comprehensive, sensitive, and state-of-the-art methods to identify all putative off-target sites by identifying places where a Prime Editor has a possibility (no matter how small) to nick the DNA. We have developed multiple, complementary, but distinct, methods to measure such possible events. Our approach includes evaluation of: (a) off-target activity in the genome that is specific to the sequence of a particular pegRNA or the ngRNA; (b) similar activity that is independent of the pegRNA or ngRNA sequences; and (c) genomic rearrangements.

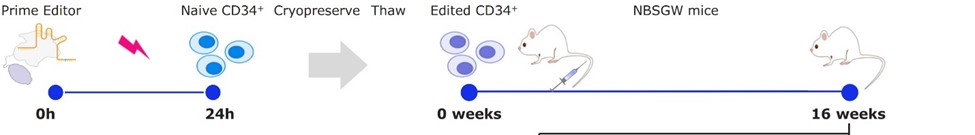

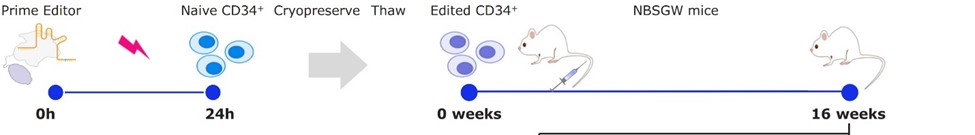

•Electroporation: Electroporation is a clinically and commercially validated technology for ex vivo delivery to CD34+ cells which utilizes electrical pulses to increase the cell membrane permeability to deliver the Prime Editing components. Electroporation is being used in our CGD program with ex vivo CD34+ cells. We have established a modular cell processing manufacturing platform process that can be used for autologous CD34+ cells, and it can be leveraged for the next ex vivo HSC programs, as well as for allogeneic T-cells with multiplexing. In the future, we plan to transition to in vivo editing of stem cells and other lymphocytes.

•LNP: LNP delivery has initially focused on in vivo delivery of Prime Editing to the liver. We have established end-to-end capabilities across our R&D organization consisting of lipid design, lipid synthesis, high throughput LNP discovery from our proprietary lipid library using screening with bar coding technology, LNP formulation process development for tissue targeted delivery, and manufacturing to support our preclinical and IND enabling studies. We are developing a universal liver targeting LNP comprised of 5 components and plan to leverage its modularity for our various programs aimed at Prime Editing in the liver, as well as to address additional mutations within the same indication. Similar approaches are being taken for developing modular LNPs to lung, and HSCs and T cells.

•Viral Delivery: We are using viral delivery to tissues and locations that can currently only be reached with AAV. To enable this delivery approach, we have developed capabilities to design and optimize the vector genome to efficiently deliver Prime Editors to the target tissue. We use our internal AAV Reagent Production Core, analytical development team, as well as outsourced resources and partners to generate AAV Prime Editors, quality control test as well as characterize them.

•Strategic Manufacturing Partnerships: Our overall strategy is to design manufacturing platforms to make the Prime Editing components and associated delivery systems with high throughput, high quality, high purity, modularity, and scalability. We are developing manufacturing processes and analytical methods both internally and partnering with suppliers to ensure the quality and consistency of the Prime Editor components and Prime Edited drug products needed for preclinical studies, IND application submission, and future clinical studies.

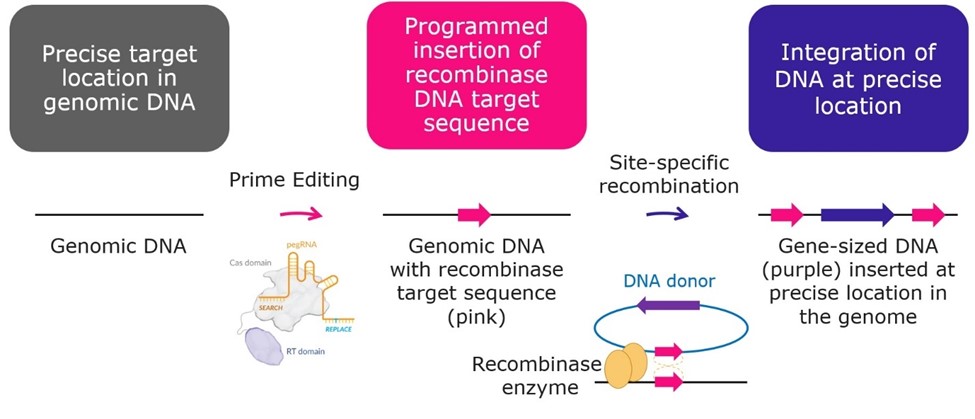

Our Pipeline

To maximize the potential of our Prime Editing technology, we have built a diversified portfolio of investigational therapeutic programs organized around core areas of focus: hematology and immunology, liver, lung, ocular, and

neuromuscular. We are advancing additional programs as potential partnership opportunities. The following table summarizes the status of certain of our programs:

Our Blood Programs

Chronic Granulomatous Disease

The Disease

Chronic granulomatous disease, or CGD, is a rare inherited hematologic disorder characterized by susceptibility to severe, difficult-to-treat infections, and inflammatory/autoimmune complications. CGD is caused by mutations in any one of the subunits comprising the NADPH oxidase complex, which is required for phagocytic cells, in particular neutrophils, to destroy many invasive microorganisms. CGD causative mutations are estimated to occur between one in 100,000 and one in 200,000 births in the United States, and most children are diagnosed within the first three years of life. Beginning in childhood, patients with CGD develop infections from a range of both typical and unsual bacteria, fungi and mycobacteria. These infections may present in various organ systems, and protracted infections can lead to long-term organ damage and failure. In addition, patients have non-infectious inflammatory disease, most commonly presenting as inflammatory bowel disease, soft tissue granulomas, and strictures of the urinary or digestive tract. Undiagnosed or untreated, the infectious manifestations of CGD are rapidly fatal. Approximately 60 percent of patients with CGD reach age 30 and refractory or antimicrobial resistant infection is the leading cause of mortality.

The NADPH oxidase complex has five domains encoded by five separate genes. Loss-of-function mutations in any of these genes can present as CGD. The second most common form, which represents approximately 25 percent of cases, is caused by biallelic loss-of-function mutations, in both copies of the NCF1 gene encoding the p47phox protein. More than 78 percent of p47phox CGD patients have a specific, 2-nucleotide deletion, or ΔGT, in the NCF1 gene. The NCF1 gene location is complex, and also contains pseudogenes, or copies of the NCF1 gene that in most healthy individuals, and in individuals with CGD, are inactivated by the ΔGT mutation. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that correcting just one copy of the ΔGT mutation in either the NCF1 gene or any pseudogene restores protein expression and full NADPH oxidase activity.