and Neurocrine. Since our inception, our operations have focused on organizing and staffing our company, business planning, raising capital, establishing our intellectual property portfolio, determining which neurological diseases to pursue, advancing our product candidates including delivery and manufacturing, and conducting preclinical studies and clinical trials. We do not have any product candidates approved for sale and have not generated any revenue from product sales. We have funded our operations primarily through private placements of redeemable convertible preferred stock, public offerings of our common stock, and our strategic collaborations, including our collaboration with Sanofi Genzyme, or the Sanofi Genzyme Collaboration, which commenced in February 2015 and was terminated in June 2019, our collaboration with AbbVie focusing on tau-related diseases, or the AbbVie Tau Collaboration, which commenced in February 2018, our collaboration with AbbVie focusing on pathological species of alpha-synuclein, or the AbbVie Alpha-Synuclein Collaboration, which commenced in February 2019, and our collaboration with Neurocrine Biosciences, or the Neurocrine Collaboration, which commenced in March 2019.

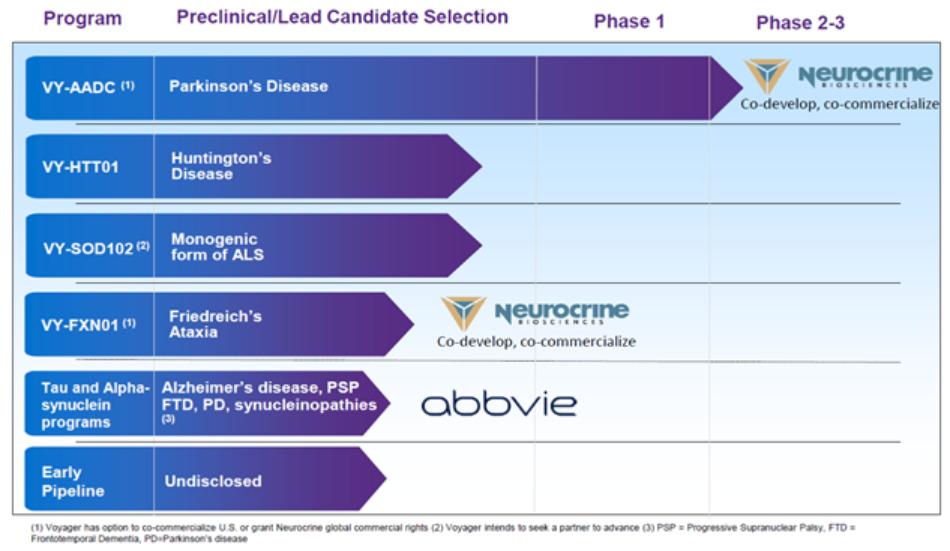

Our pipeline of gene therapy programs is summarized in the table below:

Our pipeline consists of programs for severe neurological indications, including Parkinson’s disease; Huntington’s disease; a monogenic form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS; Friedreich’s ataxia; tau-related diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, or FTD, and progressive supranuclear palsy, or PSP; and alpha-synuclein related diseases for Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. We may seek orphan drug designation, breakthrough therapy designation, or other expedited review processes for certain of our product candidates in the United States, Europe, and Japan.

Our most advanced clinical candidate, VY-AADC for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease is included in our collaboration agreement with Neurocrine. We are evaluating the delivery of VY-AADC in a transfrontal (i.e., top of the head) surgical delivery route in a Phase 1b clinical trial, and separately, we are exploring the delivery of VY-AADC using a posterior trajectory (i.e., back of the head surgical delivery route) in a Phase 1 clinical trial (PD-1101 and PD-1102, respectively). PD-1101 is an open-label, dose-ranging, Phase 1b clinical trial for VY-AADC to evaluate safety and efficacy. We enrolled 15 patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease and assessed increased volume or concentration of VY-AADC in three separate cohorts consisting of five patients in each cohort. PD-1102 is a separate, open-label, Phase 1 clinical trial exploring a posterior (i.e., back of the head) surgical delivery route for VY-AADC that enrolled eight

38