Filed pursuant to Rule 433 |

Investable Indexed Approaches

To Long/Short Investing

Factor- and mechanical-based replication methods

By Peter Little and Greg King

This article relates to certain Credit Suisse indices and not to any specific Credit Suisse security linked to those indices. Returns on the indices are not the same as returns on any such security, which may be burdened by additional fees and charges. Credit Suisse AG (“Credit Suisse”) has filed a registration statement (including prospectus supplement and prospectus) with the Securities and Exchange Commission, or SEC, for certain offerings to which this communication may relate. Before you invest, you should read the applicable prospectus for more complete information about the issuer and the securities and other considerations that are important in making a decision about investing in the securities. You may get these documents without cost by visiting EDGAR on the SEC website at www.sec.gov. Alternatively, Credit Suisse, any agent or dealer participating in an offering will arrange to send you the applicable pricing supplement, prospectus supplement and prospectus if you so request by calling toll-free 1 (800) 221-1037.

22 May

/ June 2012 May

/ June 2012 | |

The term “long/short” (LS) has wide and varied applications in the world of investments. In its broadest definition, an LS strategy signifies an investment process not constrained to holding only long positions. In perhaps its most common usage, an LS fund tends to refer to an equity hedge fund that takes both long and short positions. Whatever the application of the term, LS investing usually implies a search for absolute returns and an attempt to decrease or neutralize market beta. This combination of absolute returns with low market beta can also be described as “alpha” and has historically been considered an “active” investment approach. Here we examine the LS investing landscape from the perspective of an indexer. We make the case that there are sensible and investable ways to index these strategies, thereby creating a “passive” approach to various sectors of LS investing.

Certain questions arise in such an undertaking: Which types of strategies are suitable for indexing and which are not? What are the pitfalls of index construction when considering long/short strategies? When looking at LS fund results, how can we separate those attributed specifically to the superior skill of some managers from those managers who are able to deliver purely because of the unconstrained nature of the LS investing techniques at their disposal? To address these and other questions, we first provide an overview of the four main types of LS models. Next, we examine the case for passive approaches to LS investing. Finally, we present case studies of the Credit Suisse long/short index as an example of factor-based replication and the Credit Suisse merger arbitrage index as an example of mechanical replication.

The Long/Short Landscape

Whenever a manager decides to pursue a long/short strategy, her investment approach can be distilled into one of four models by answering certain questions about the approach: Are positions taken based on company- or issue-specific information? Are decisions primarily based on the outputs of a quantitative model or do they come from fundamental research? Is there a high or low degree of turnover?

There are four basic models used for selecting long/ short positions in these strategies:

• Valuation

• Trend-following

• Macroeconomic

• Arbitrage

Valuation-based approaches are typically buy-and-hold strategies. The manager selects undervalued securities for the long side of the portfolio, and overvalued securities for the short side. Generally this approach leads to more stable positions with lower turnover than other strategies. Alpha in this space is derived from fundamental analysis of securities. Managers have a high amount of discretion in the selection process and focus on company fundamentals more than on the macro environment. Typically, these managers are long biased and, in addition to potential alpha from security selection, add value by

varying their market exposure to deliver beta in a generally more efficient or better risk-adjusted format.

Trend-following models use technical indicators to identify trades. Typically, managers in this space use quantitative or systematic processes to generate buy or sell signals and have somewhat limited discretion in these decisions. This is a market-timing approach and is suitable across asset classes so long as the instruments traded are liquid. In addition, managers prefer instruments that are not company specific so as to remove idiosyncratic risk from the model. Returns from trend-following strategies are typically relatively uncorrelated to traditional beta, providing investors with diversification as well as the potential for alpha from the superior market timing of some managers’ models. A “managed futures” strategy would be an example of this approach.

Macroeconomic-based approaches are cross-asset-class in nature and are driven by global macroeconomic trends. Similar to trend-following approaches, they use liquid instruments that are not company specific and have a fairly high degree of turnover. Alpha in this space is derived from market timing. As with trend following, these managers invest across a variety of asset classes and can have net long or short exposures, so in addition to potential for alpha from superior market timing, these managers offer investors diversification to their traditional exposures. Managers take into consideration a variety of information that could affect the economy, either on a relative basis (e.g., long/ short country pairs) or on an absolute basis (e.g., expect a global downturn and go short risky assets). Data that managers factor into their decision-making process are likely to include anything that could impact the local or global economy, including economic releases, political environment, supply/demand and a variety of other information. Managers in this space also use relative value techniques to extract diversified risk premia like currency carry. A “global macro” manager would be an example of this approach.

Finally, arbitrage strategies seek to exploit relative pricing inefficiencies in different markets or securities. They focus on issuer-specific securities, and generate alpha from security selection. The strategies are risk-managed in a quantitative approach, and tend to be market neutral. As such, they provide good diversification to traditional exposures based on the managers’ ability to extract uncorrelated risk premia. Managers will look to identify different securities that should have a strong relationship (based on some shared characteristics) but that are temporarily valued differently (e.g., convertible bonds that should theoretically have a similar value to a combination of the company’s debt and options on its stock). Managers then take a relative value position in those securities in order to profit as their values converge.

Indexing Long/Short Investment Strategies

To answer why indexing is worthwhile for LS investments, we need to look at what it accomplishes. First, the investable indexing process removes manager-specific alpha. This idiosyncratic risk is nearly impossible to index and tends to

| www.journalofindexes.com | May / June 2012 23 23 | |

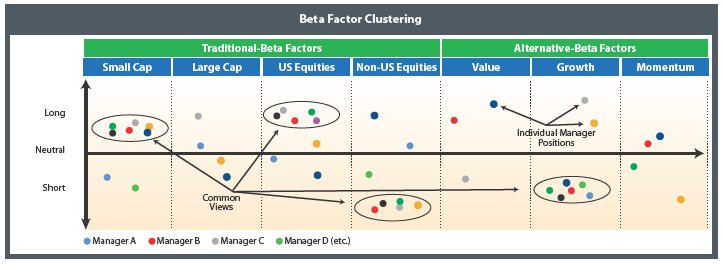

Figure 1

Source: Credit Suisse Asset Management, LLC

be diversified away through most index processes. What then remains are the alternative betas. These risk premia—such as relative value arbitrage, long positive trends versus short negative trends and the ability to introduce leverage to create convex return profiles—are available only in the universe of LS investing. Removing the long-only constraint of the traditional indexing approach brings this access to new risk premia. In trying to index the strategies of a certain style of long/short investing, the indexer is essentially trying to systematically capture the main benefits of the strategy beyond manager alpha and deliver a new “passive” source of returns to investor portfolios.

Long/short strategies are typically indexed either by observing actual hedge fund returns in the sector or via various replication strategies. Although aggregation of hedge fund returns data is an approach that has been taken by a handful of firms and is useful for many purposes, including research, the approach does not generally lend itself to investability. Various constraints may stand in the way of broad investability here, such as a lack of daily liquidity, limited access to certain funds, capacity constraints of certain funds, and investor class constraints, to name a few. Conversely, replication strategies—of which there are two main types—tend to start with investability in mind.

Factor-Based Replication

The first replication style, “factor-based replication,” uses quantitative measures to attempt to replicate hedge fund index returns by defining models that bear a high correlation to the hedge fund index return stream. Factor-based replication tries to identify both the market segments (“factors”) and the level of current risk that managers currently favor. Such models only “invest” in liquid market betas (and alternative betas) rather than the hedge funds themselves. This replication method is typically used in fundamentally based strategies where exposures are expected to be more stable.

Factors are typically proxied using a basket of securities that represent a certain risk premium, e.g., U.S. large-cap

equities (e.g., S&P 500), value companies (e.g., Russell 2000 Value Index), high-yield bonds (e.g., iBoxx Liquid High Yield Bond Index), etc. Factors can also represent certain investing behaviors, such as price momentum, to which managers can be exposed when they become susceptible to performance chasing. These can be proxied by creating a factor that buys securities that have been going up and shorts securities that have been going down. Finally, factors can also represent a type of risk that managers can become exposed to by nature of the instruments they invest in; for example, illiquidity risk, which managers take on when they invest in securities that are difficult to sell. This risk can be interpreted as short exposure to volatility, since managers are likely to be paid a premium for holding illiquid securities while being susceptible to sharp losses in volatile environments when illiquid securities are likely to trade at steep discounts. This factor can be proxied by selling options that give a similar profile of being short volatility (and risking sharp losses if volatility spikes) while earning a premium over time.

To empirically determine the market factors that drive LS equity hedge fund returns, two key assumptions are made. The first, “view commonality,” suggests that managers tend to have clustered “views” (defined as exposures to various beta and alternative beta market factors). Analysis of actual hedge fund holdings shows this type of clustering exists. (See Figure 1.) The second and corollary assumption, “exposure inertia,” holds that, on average, managers will adjust these exposures to market factors fairly slowly—a few managers tend to adjust their exposures first, then, if their views turn out to be correct, others tend to follow. This exposure inertia allows multifactor-based replication models to identify and track the changes in the core factors over time. However, as factor-based replication relies on these assumptions about the behavior of managers when they encounter certain environments, these types of models can be slow to adapt to systemic changes in the way managers, in general, react to new environments in the future.

24 May

/ June 2012 May

/ June 2012 | |

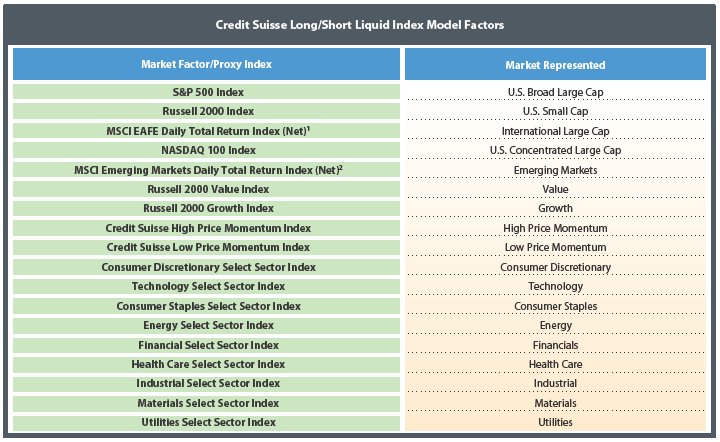

Figure 2

Source: Credit Suisse Asset Management, LLC

Case Study – Factor Based Replication (Credit Suisse Long/ Short Liquid Index)

The Credit Suisse Long/Short Liquid Index uses factor-based replication to achieve a high correlation to the equity long/short segment of the hedge fund universe (as represented by the Dow Jones Credit Suisse Long/Short Equity Hedge Fund Index, which we refer to as the ”target index”) in an investable way.

In this case, Credit Suisse designed a stepwise multiple regression process to determine the markets in which long/short equity managers are investing, identify the amount of risk long/short equity managers are taking and capture these exposures, as reflected in the performance of the target index, using the liquid instruments that correlate to the target index.

The process begins with an analysis of historical performance data to identify core, broad-market exposures in which managers in the aggregate appear to have taken positions during the prior 12 months. As described previously, common manager views are the main drivers of hedge fund index performance, and these return drivers can be captured using a combination of factors. These factors are not hedge funds but are actual market indexes that are investable with reasonable liquidity. For example, U.S. large-cap exposure can be proxied by the S&P 500 Index, while equity momentum can be proxied by an index representing long positions in companies that are performing well and short positions in poorly perform-

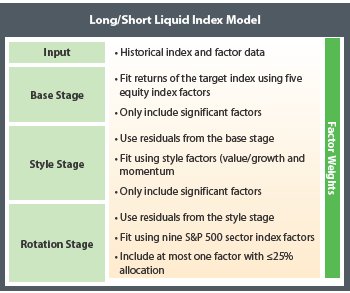

Figure 3

Source: Credit Suisse Asset Management, LLC

ing companies. Once identified, core factors are selected from specified liquid tradable indexes. Exposures to these indexes can be long or short, with net exposures changing monthly depending on the market environment.

An overview of the factors used by the long/short model is shown in Figure 2.

The model estimates factor weightings by performing a stepwise regression of index returns on factor returns. A stepwise regression is similar to an ordinary least-squares

| www.journalofindexes.com | May / June 2012 25 25 | |

(OLS) regression regression, but with one main advantage—it identifies and retains only those factors deemed to be statistically significant return drivers. This procedure is important because it avoids allocating to less relevant factors, while trying to mitigate the effects of factor co-linearity resulting from the statistical similarity of many of these equity factors.

Next, as illustrated in Figure 3, the model analyzes the extent to which the returns of the hedge fund index that were not explained by stage one are attributable to dynamic market-neutral-style trades. The model examines the difference between the performance of the hedge fund index and the performance of the core exposures and fits these residual returns using a stepwise regression.

Finally, the model seeks to identify which short-term, industry-specific trades are driving the hedge fund index returns in excess of the core exposures and the dynamic style themes. Once again, in employing a stepwise regression, this time over a short time horizon, the model identifies which industry sector best explains the previously unexplained returns. In this stage, the regression is constrained to select only one factor in order to identify the single most important exposure and to avoid over-fitting the model.

This process is performed every month as the most recent hedge fund index returns are available. These three stages identify the factors that should be included in the replication model in any given month, as well as how much weight the factor should be assigned. The LS equity replication index is then calculated based on the performance of the factors determined by this process. Overall, the results demonstrate the potential available in this type of an approach: Since inception, the Credit Suisse Long/Short Liquid Index has had an annualized return of 5.5 percent versus a return of 3.7 percent for the target hedge fund index (the Dow Jones Credit Suisse Long/Short Equity Hedge Fund Index) and has had a 92.8 percent correlation to the target index.3

Mechanical Replication

The second replication method, “mechanical replication,” skips using hedge fund returns completely. Rather than seeking to correlate to a target index or segment, this method’s purpose is to fully replicate, if possible, the particular LS strategy in question by systematically mimicking the trades managers in that strategy make. Mechanical replication is used where the investing technique is well defined and the universe of securities is identifiable, investable and not excessively large. This approach seeks to define the strategy and implement rules around how it should be carried out in a defined universe of investments.

For example, the “carry” strategy in currency investing can be mechanically replicated. The carry technique involves going long high-yielding currencies while simultaneously shorting low-yielding currencies, implicitly wagering that forward rates will not converge to their then-current levels. To replicate this mechanically, a set of rules regarding when to buy/sell a particular currency could be defined, and a universe of tradable cur-

Figure 4

Source: Credit Suisse Asset Management, LLC

rency pairs could be identified upon which to execute the indexed strategy. Another strategy that is conducive to mechanical replication is managed futures, where the universe of securities that managers trade is identifiable (typically liquid listed futures contracts) and the technique is well defined (i.e., investing in pricing trends, typically momentum-based trends over a variety of different trend horizons). This strategy can be systematically mimicked with a generic trend-following model that uses a variety of liquid futures contracts and trend horizons to determine the trading strategy.

While mechanical replication is appealing because of its straightforward nature and lack of correlation assumptions, there are unfortunately relatively few sectors of LS investing where it is reasonably possible.

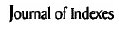

Case Study: Mechanical-Based Replication (Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Liquid Index)

The Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Liquid Index (the “merger index”) serves as an example of mechanical replication. Merger arbitrage involves capturing the spread between the price at which the stock of a company trades after the announcement of a proposed acquisition of that stock and the price that the acquiring company has proposed to pay for it. The spread typically exists due to the uncertainty that the announced merger or acquisition will close, and, if it closes, that such merger or acquisition will take place at the initially proposed economic terms. For successful transactions, the spread is expected to approach zero by the closing date of the transaction. The size of the spread itself depends on the perceived risk of the deal closing, as well as the length of time expected until the deal is completed.

All of these factors lend themselves to mechanical rep-

26 May

/ June 2012 May

/ June 2012 | |

lication. The merger index uses a quantitative methodology (see Figure 4) to select a diversified sample of liquid merger arbitrage deals in order to represent the returns of the merger arbitrage space.

The selection process begins once a new deal is announced. The model determines each deal’s eligibility for inclusion in the index; eligible deals can involve bids offering cash, stock or some combination of both in exchange for the target’s stock. In cash deals, the target’s stock typically trades slightly below its bid price immediately following the deal announcement and moves toward bid price as the probability of deal closing increases. In an eligible cash deal, the merger index will “buy” the target. In stock deals, the price of the target and acquirer typically trade at a spread post-announcement and converge as the probability of deal closing increases. In an eligible stock deal, the merger index will “buy” the target and “short” the acquirer.

To ensure the investability of the merger index, the process focuses on the deals that are likely to be liquid. Specifically, this means the deal universe is limited to deals in Western Europe and North America, where deal activity is highly regulated, and as such typically allows for more orderly trading. In addition, these companies are more likely to have larger market capitalizations and meaningful trading volumes, and therefore their stock should be easier to borrow (in the case of acquiring companies that need to be shorted in the index).

Once the eligible universe is defined, constraints are applied to ensure there is sufficient arbitrage potential, i.e., to ensure that the offer is for most or all shares outstanding and that the acquirer does not already own the vast majority of the target company stock.

Once selected, deals are generally held in the index until they are completed or officially terminated (occasionally deals will be removed if they breach liquidity constraints, such as if the acquirer’s stock is no longer easy to borrow).

The merger index takes the approach of holding deals as long as possible because when a deal is removed based on stop-losses, maximum deal spreads or time constraints, such removal often simply crystalizes any negative performance while removing any possibility of recovery, rather than tracking the potential future success of the deal.

The index is rebalanced daily and risk constraints are applied. As for weighting, the algorithm weights deals based on the cube root of their market cap relative to the cube root of the market caps of the eligible universe. This is done to reflect the fact that, inevitably, larger amounts of merger arbitrage capital are able to be deployed in the larger deals while recognizing that occasionally, there can be a 100-to-1 ratio in deal sizes and therefore some scaling is desirable. All deals are capped at a maximum weight of 7.5 percent within the merger index to avoid over-concentration in large deals.

The merger index uses this passive approach to extract the merger arbitrage risk premium and diversification benefits of merger arbitrage investing from a large and defined universe of potential deals. It has generated positive returns in both years since its inception in 2009, with an annualized return of 4.9 percent.4

Conclusion

Despite the perception of long/short investment strategies as “active,” it is possible to capture the performance characteristics of certain strategies in this category through a passive approach. By providing examples of Credit Suisse indexes that rely on factor-based replication and mechanical replication, respectively, we have demonstrated how these very different methods reflect the underlying market trends that drive the performance of the targeted strategies. The resulting indexes, which reflect investable executions of these strategies, provide examples of how indexing can provide a passive alternative to these traditionally “active” investment strategies.

Endnotes

1 In the case of a negative weight for this market factor, the gross index version of this market factor will be used.

2 Ibid.

3 Data as of 2/29/12. Represents performance of the Credit Suisse Long/Short Liquid Index from 10/16/09, the inception date of the index, to 2/29/12. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.

4 Data as of 2/29/12. Represents performance of the merger index from 12/31/09, the inception date of the merger index, to 2/29/12. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance.

Disclosures

For more information on these indices, including information about their historical performance, as well as information about certain securities being offered by Credit Suisse that link to these indices, see www.credit-suisse.com/etn and you may access the pricing supplements relating to some of these securities on the SEC website at: Credit Suisse Long/Short Equity Index Exchange Traded Notes: http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1053092/000110465912020682/a12-7748_1424b2.htm Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Index Exchange Traded Notes: http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1053092/000095010312001483/dp29447_424b2-etn3a.htm Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Index Leveraged Exchange Traded Notes: http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1053092/000095010312001484/dp29449_424b2-etn4a.htm Before investing in any these securities, you should, in particular, review the “Risk Factors” section in the applicable pricing supplement, which sets forth risks related to an investment in the securities.

The indices have limited history and may perform in unexpected ways. The performance of the Credit Suisse Long/Short Index and the Credit Suisse Merger Arbitrage Index may not be entirely representative of the performance of their respective strategies, and there is no assurance that the strategy on which these indices are based will be successful. Additionally, because Credit Suisse is affiliated with the sponsor of the indices, and certain of its employees are members of the index committees for the indices, conflicts of interest may exist between Credit Suisse and investors in securities whose return is based on the indices.

| www.journalofindexes.com | May / June 2012 27 27 | |